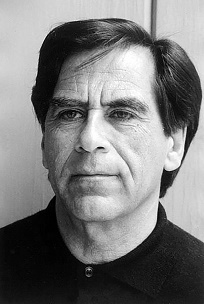

Robert Pruger

Professor of Social Welfare, Emeritus

Professor Robert Pruger was born on January 10, 1933 in New York City. He died on December 4, 2020 after a long illness. He received his bachelor’s degree from CCNY in 1954 and his MSW from the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work in 1957. He then went to work for The Vacation Camp for the Blind, a year-round organization that provided social services to blind and deaf clients. He left VCB to work for Mobilization for Youth, an anti-juvenile delinquency program on the lower east side of New York. In 1965 he worked for the California Health Department in their Social Service Department. He received his DSW from the School of Social Welfare at the University of California at Berkeley where he was hired in 1966 and remained until his retirement in 1993.

Professor Pruger's key research interests were the organization of welfare programs and the contribution of economics to these programs. Professor Pruger was an expert in bureaucratic organizations and social welfare. He was interested in improving the way social welfare programs worked. Bright and open minded, he believed that economic thinking could advance the field. Significant progress was made by Professor Pruger toward understanding the major types of welfare programs: care and recovery; their divisions of labor, and the roles of each division in each type of program; what information each division needed to effectively carry out their roles and how perfectly functioning programs would operate in each category; the resource allocation rules in each; how each should be evaluated and how research could improve the effectiveness and efficiency of these different types of programs.

The division of programs into care and recovery is important because social work efforts in practice differ by division. Allocation of care efforts proceeds from the neediest to the less needy. Allocation of recovery should proceed from the most likely to make use of an effort to the least likely to make use of it. While efforts resulted in a series of important publications, Professor Pruger did not consider himself very successful at getting the field to pay attention to these ideas. There were political constraints to progress; many social welfare programs were paid for by the state, and improvements to welfare programs did not seem to be high on a new political regime's agenda. In spite of some successes, it was an upstream swim all the way.

Professor Pruger was fascinated that organizations did not realize the discretion they had in the creation of welfare programs. To explore this idea, he formed an ongoing monthly seminar with five Bay Area Welfare Directors. The objective was to communicate about discretion and to see how the University could help find solutions to the directors’ perceived problems with welfare programs. Professor Pruger, together with Professor Leonard Miller and three doctoral students (Marlene Clark, Jackie Jew, and Maddie Helm), addressed the directors’ most important problem: In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS). IHSS provided support for poor elderly Californians to improve their well-being and to keep them out of, or delay, their entry into nursing homes. This was a billion dollar per annum State program in 1970, carried out by the counties. Neither the State, nor County Departments knew how the program should run.

Three program unknowns required inquiry: 1. how counties should organize the processing of information about clients; 2. whether counties should provide clients with less expensive helpers so that more hours could be allocated, or, more expensive, skilled, courteous, punctual workers with less hours of work, because their compensation would be higher; and 3. how the program could be fair in distributions of hours. In her dissertation about the administration of the program, Jackie Jew found that there was virtually no difference in the administrative costs of the program among all five counties. In her dissertation, Maddy Helm found that the clients had a clear preference for more hours of help versus any niceties about the personnel providing the services.

The fairness question was the most interesting. With Radio Shack computers, the relationship between the program’s client assessment tool and the hourly awards was investigated. It was found that implicit award rules were different in every county. Hence communication about assessment questions and how the program should compensate clients for different types of needs had to improve. In her dissertation, Marleen Clark reported the following next steps. Wes Boyd, the son of a Social Welfare colleague, then Professor Larry Boyd, wrote an algorithm that put the assessment information into a database, provided a predicted hour awards, and asked the agent what award was actually made. If there was a significant difference between the predicted and the actual award, the algorithm asked the agent to write a short explanation. Professor Pruger kept track of the significant differences and related explanations and in monthly meetings with the agents, led discussions to clarify and resolve these differences. One example from those meetings was that deaf clients received fewer hours; apparently, they didn’t complain about their awards. Agents were alarmed at their own behavior and made efforts to solve this problem. Perhaps the largest variations came in the awards made to quadriplegic clients. Some agents argued that mobility was already part of the assessment; others argued that quadriplegics had whole level more of severity in their mobility. As a result of the discussion agents agreed that quadriplegics would receive 20 more hours per month. After three iterations of assessments, changes to the assessment forms, changes in the distributive algorithms, and monthly meetings about unresolved differences, variations in distributions decreased, program agents were being more similar and fairer in carrying out the program. One agent told Professor Pruger that this was the first time in her career that she felt she had influenced the development of a program.

It would have been logical to attempt to get all five counties to use the same distributive algorithm, but the program managers wouldn’t allow that to happen. Professor Pruger took a sabbatical leave in Sacramento in an effort to obtain legislative support to incorporate what the group had found in the large State program. The Democrats had lost the last election and IHSS was not on the priority list of the new administration. Many years later the group’s efforts became the basis for rationalization of the program.

Professor Pruger’s research is notable for its focus on social service programs that affect clients, its focus on fairness and using state-of-the-art technology of the time to try to increase fairness in distribution, for its integral involvement of doctoral students in this programmatic research and in his efforts to influence legislators by his physical presence in the State Capitol.

Professor Pruger collaborated with Professor Eileen Gambrill in publishing a series of books debating controversial issues in social work. Each debate included a pro and con statement as well as a reply to the other’s statement – a unique feature of these books. These included two books they edited, Controversial Issues in Social Work (1992) and Controversial Issues in Social Work Ethics, Values and Obligations (1997). In addition, they arranged publication of similar books by other editors.

Professor Pruger offered a unique course "The Good Bureaucrat" emphasizing that administrators could be valuable contributors to offering clients high quality services. One of the students described this course:

Professor Pruger encouraged us to think about complex social issues and advocate for one point of view while also thinking about how to argue for the opposing point of view. He was interested in each student's perspective without any defensiveness.

Bob Pruger was devoted to his family. He loved Beethoven. He enjoyed discussion – if it increased the possibility of understanding the social institutions and structures that form the basis for our understanding of reality. He leaves his wife Naomi and three children, Michael (Karen), Joseph (Shelli) Pruger and Amy Dyckovsky. He has eight grandchildren, Lucas, Sarah, Jacob, Zevi, Shael Pruger, and Ari, Max, and Rachel Dyckovsky and one great grandchild, Matthew Pruger.

Leonard Miller

Eileen Gambrill

2021