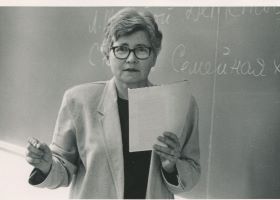

Olga Raevsky-Hughes

Professor Emerita of Slavic Languages and Literatures

For three decades, Olga Raevsky-Hughes brought her deep understanding of Russian culture to generations of students at the University of California at Berkeley and made significant contributions to the study of twentieth-century Russian literature, both in Russia and in the emigration. A path-breaking researcher and dedicated teacher, she was a person of exceptional modesty and quiet dignity, devoid of self-importance and utterly dedicated to the service of others.

Olga Raevsky [Ольга Петровна Раевская] was born in 1932 in Kharkiv (then, in Soviet Ukraine), the daughter of Petr Nikolaevich Raevsky and Nadezhda Panteleimonovna (Savchenko). During World War II, soon after that city was occupied by the German army, the family made a perilous journey across Europe, via Prague (where Olga briefly attended a Russian school) to Munich, where, in 1945, they joined the ranks of displaced persons (DPs) in the American zone of occupied Germany. Living under precarious conditions–recent arrivals risked being deported back to the Stalinist Soviet Union—Olga graduated from a remarkable Russian gymnasium opened in Munich for displaced children and youth. In 1949 the family was able to immigrate to the US, arriving in San Francisco. To the end of her days, Olga spoke with intense gratitude about the people who helped their escape and survival.

As the family made the difficult transition to life in the US (her father, a medical doctor, was not granted the right to practice and found work as a laboratory technician and eventually as a pathologist), Olga was able to attend the University of California, graduating in 1954 with a major in biology and a focus on bacteriology. Preparing for a medical career, in the footsteps of her father, she worked in a lab; then, in 1960, she decided to pursue her love for Russian literature and culture in the graduate program in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Berkeley, earning a Ph.D. in 1967. She was mentored, among others, by the prominent scholar of the Russian emigration, Gleb Struve. Based on her PhD dissertation, her first book, The Poetic World of Boris Pasternak, a synthesizing study of Pasternak’s views on art and the artist’s responsibility to the world, was published by Princeton University Press in 1974. Olga’s work on Pasternak continued for many decades.

Much of Olga Hughes's life was linked to the University. She taught at Berkeley from 1967 until her retirement in 1993, first, as a lecturer, teaching Russian language, later, as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor and Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. She served the University also as Department Chair and Associate Dean of Students. In addition, she served the Academic Senate as a member of the Student Affairs Committee in 1975-76, the Educational Policy Committee in 1978-79, and Committee on Courses of Instruction (COCI) in 1982-85.

In graduate school, Olga met her future husband, Robert Hughes, who became her colleague at Berkeley, and over the years they collaborated on several research projects, including (with Lazar Fleishman), an important collection of archival texts documenting the cultural life of the early Russian emigration, Russian Berlin, 1921-1923 (Russkii Berlin, 1921-1923, Paris: YMCA, 1983, 2nd ed: Paris: YMCA-Press – Moscow: Russkii put’, 2003). Another collaborative project resulted in a three-volume collection of scholarly articles on religious culture, Christianity and the Eastern Slavs (co-edited with Boris Gasparov, Robert Hughes, and Irina Paperno, Berkeley: California Slavic Studies, 1993-1996).

Olga Hughes's extensive research on the work of the émigré writer Aleksei Remizov resulted in a number of publications, including the scholarly edition of his previously unpublished work Iveren', which appeared in the series Berkeley Slavic Specialties in 1986. The cultural heritage of the Russian emigration owes much to her work on this important volume, which was painstakingly edited and annotated on the basis of the original manuscript. Her edition of the text was reprinted in volume 6 of Remizov’s collected works (Sochineniia), which appeared in St. Petersburg after the end of the Soviet regime (Moscow: Russkaia kniga, 2000). As a leading specialist in the study of Remizov, she was invited to join the editorial board of this multivolume edition at the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkinskii Dom) of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Another highly significant publication of previously unknown archival documents, Vstrecha s emigratsiei. Iz perepiski Ivanova-Razumnika 1942-1945 godov [An Encounter with the Emigration. The Selected Correspondence of Ivanov-Razumnik with Émigré Writers] (Paris: YMCA Press; Moscow: Russkii Put’, 2001), documented a unique moment in the history of the Russian culture: an encounter between the two worlds separated by the Russian revolution. It occurred when the prominent writer Ivanov-Razumnik, who had remained in the Soviet Union after 1917, was interned in a camp on occupied territory during World War II and entered into correspondence with his former friends and colleagues on the other side of the previously impenetrable divide. For Olga, this topic was deeply meaningful; for more than twenty years she was an active member of the committee “Books for Russia,” which was engaged, initially clandestinely, in making émigré editions available to Russians both before and after the fall of the Soviet regime. Olga also enlisted as the West coast representative for the Library of the Russian Emigration, collecting and shipping émigré archives back to Russia. Notwithstanding the present fraught relationships between Russia and the outside world, this unique and vital research institution and library in Moscow, now renamed the Solzhenitsyn House for the Russian Emigration (Dom russkogo zarubezh'ia imeni Aleksandra Solzhenitsyna) continues to operate.

An important part of Olga’s work was connected with Russian religious culture and the Russian Orthodox Church. A participant in the Russian Student Christian Movement [РСХД] since her gymnasium years in Munich, she was an active presence as an author and editor in its journal, Vestnik RSKhD, an important forum for discussions of Russian religion, culture, and society, which has remained in operation, in the diaspora, from the 1920s to this day. Olga sat on the governing board of the Ivan V Koulaieff Foundation, the important Russian philanthropic organization based in San Francisco, from 1974 to 2009, and was the first and so far only woman to serve as its President, from 1999 to 2009. Her dedicated and generous service to the Russian Orthodox Church was recognized by the Order of St. Innocent awarded to her in 2002 by His Beatitude, Metropolitan Theodosius of the Orthodox Church of America.

In the later part of her life, Olga revisited the experiences of her early years, publishing, with fellow students from those days, two collections celebrating their teachers in the Russian gymnasium in Munich (Sud'by pokoleniia 1920-1930-kh godov v emigratsii [The Lives of the 1920-1930 generation of emigration] and "Nastavnikam, khranivshim iunost’ nashu..." [To the Teachers who Cherished our Youth], which appeared in 2006 and 2017 respectively from the publisher Russkii put' in Moscow.

For much of her long life, Olga Raevsky-Hughes worked to recover, reconstruct, and preserve the culture endangered by the cataclysms of history that had shaped her own life and that of her contemporaries in the Russian emigration. She worked tirelessly and selflessly to connect two worlds–inside and outside Russia–which had long been separated by political, cultural and generational divides. As her colleagues, the late Hugh McLean and Simon Karlinsky, wrote in the 2006 Festschrift dedicated to Olga and Robert Hughes, “she has done more to advance awareness and understanding of Russian literature than many others more adept at self-promotion.”

Olga Hughes died in her Berkeley home on August 3, 2023. She is survived by her husband.

She will be warmly remembered by many, including her grateful colleagues at Berkeley.

Eric Naiman

Irina Paperno