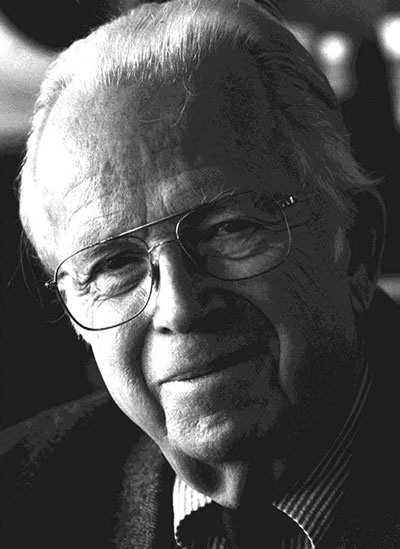

Neil Joseph Smelser

University Professor

Professor of Sociology, Emeritus

Neil Smelser was a man of extraordinary accomplishments in scholarship and service. Born July 22, 1930, on his grandparents’ farm in rural Kahoka, Missouri, he moved as an infant to Phoenix, Arizona, where his father taught at Glendale Community College and his mother taught high school Latin. A product of Phoenix public schools, Smelser graduated from Harvard University (1952), was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University (1952-54), and obtained the Ph.D. in sociology from Harvard in 1958. In that year he joined the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, where his rise was meteoric – tenure one year later at age 29, editor of the American Sociology Review in another two years (1961), and the sixth University Professor of the University of California in 1971, giving him status and teaching opportunities on all University of California campuses.

Over nearly six decades of scholarly activity, Smelser distinguished himself in the discipline of sociology, and more generally in the social and behavioral sciences. He was a prolific author with 21 solo and coauthored books, 32 edited books, and 128 articles and essays. He made original contributions to economic sociology, British history, sociological theory, higher education, psychoanalysis, and the study of social change and collective action.

Some of his most acclaimed works include: Economy and Society (1956), Social Change in the Industrial Revolution (1961), Theory of Collective Behavior (1962), The Sociology of Economic Life (1963), Social Paralysis and Social Change: British Working-Class Education in the Nineteenth Century (1991), Problematics of Sociology (1997), The Social Edges of Psychoanalysis (1998), and Dynamics of the Contemporary University (2013). His books have been translated into many languages, including Italian, Japanese, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Russian, Greek, Korean, Turkish, and Chinese.

Smelser was engaged all his life with social scientific theory and method. Over the decades, he adopted an inclusive stance, with an emphasis on the synthesis of ideas and approaches in the task of explanation. Early in his career at UC Berkeley, from 1963 to 1971, Smelser trained at the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute and subsequently drew on this background as a therapist, author, and teacher. As he explains in the oral history conducted by the Bancroft Library (2010-2011): “It was a part of my life history that I got involved in the psychoanalytic world. It was part of my life history that triggered the event of entering into psychoanalytic treatment and training. I did not have a master plan of any kind of intellectual integration. It kind of became part of the picture as I went on. It's very consistent with my whole intellectual career. I'm always looking at some other pond in which I can put my oar and mix it up. It's thoroughly interdisciplinary. Economics, history, political science, anthropology, and psychology, including psychoanalysis, have all been in my radar, in different emphases, different weights, all through my career.”

In addition, Smelser was an astute observer of higher education itself, expressed through many articles and culminating in his 2012 Clark Kerr Lectures, which became the book, Dynamics of the Contemporary University. It was Smelser to whom Kerr turned to write the foreword to his own memoirs, The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967.

Smelser was greatly esteemed by students for his erudition, his wisdom, and his generosity of spirit (for tributes see http://sociology.berkeley.edu/neil-smelser-1958). Graduate students and faculty members have benefited from his mentorship and support. Tagged by some colleagues as “the constant diplomat,” Smelser had an immense talent for understanding complex situations and bringing together diverse views to accomplish rational and workable solutions. He was invariably friendly, unassuming, and helpful. These attributes were recognized and put to use early on as Smelser was appointed Special Assistant for Student Political Activity by Acting Chancellor Martin Meyerson in 1965 following the Free Speech Movement and amidst the intense protests the following year.

Known to be dependable, diplomatic, and shrewd, Smelser was asked to take on many more such assignments and special projects. In the late 1970s a series of reviews had placed the future of the Graduate School of Education in jeopardy. Smelser was appointed to chair a commission to recommend solutions to the issues that bedeviled the school, a chore he carried out masterfully. This was followed by Smelser’s appointment to chair a university-wide study of lower division education, a subject of much controversy and some neglect at the time. The resultant report, Lower Division Education in the University of California: A Report (1986), presented clear and viable recommendations, and has been much utilized and cited over the years. That study was later followed by a major examination of general education in public research universities, General Education in the 21st Century: A Report of the University of California Commission on General Education (2007), which Smelser defined and cochaired with Michael Schudson.

Another longtime and controversial issue for the University of California has been its management of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a responsibility dating from the original Manhattan Project in 1943. From 1989 to 1997 Smelser was a key member of high-level advisory committees to the UC president assessing the programs and operations of these laboratories. These successful acts of leadership inspired the National Academies to ask Smelser to chair a major study on behavioral, social, and institutional issues in terrorism after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Showing his leadership in yet another challenge for universities, Smelser served as chair of the Chancellor’s Blue Ribbon Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics in 1990-91. Finally, Smelser found himself in 2003 as a member of the Chancellor’s Committee on Surprises (in university leadership) and wrote a very useful essay on that study of how to deal with the unexpected. Descriptions of these activities and the relevant reports are in Smelser’s 2010 book, Reflections on the University of California: From the Free Speech Movement to the Global University.

Smelser’s calm demeanor and presence of mind during these endeavors won the respect of everyone around him. His approach during meetings was to follow discussion and mull the subject while using a multicolored pen to decorate a Styrofoam coffee cup in exquisite, and always unique, style. At the end of the meeting the cup was then a valued prize to be bestowed upon a colleague.

The Academic Senate took frequent advantage of Smelser’s gifts. He was on innumerable standing and ad hoc Senate committees, chairing many of them. He served as both chair of the Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate (1982-84) and the university-wide Academic Council (1986-87). He served as acting director of the Center for Studies in Higher Education (1987-89). Other recognitions were election to the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. He was also president of the American Sociological Association.

In 1994 Smelser retired from UC and became director of the Center for Applied Social and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, where he remained until 2001, applying visionary leadership and enabling and coordinating the stays of noted intellectuals from around the country and the world. Thereafter he returned to Berkeley, maintaining a full level of his usual varied activity.

Smelser passed away at his Berkeley home on October 2, 2017. He is survived by Sharin, his wife of 50 years, their son Joseph and daughter Sarah, as well as a son, Eric, and daughter Tina from a previous marriage, along with three grandchildren.

Judson King

Victoria Bonnell

Michael Burawoy