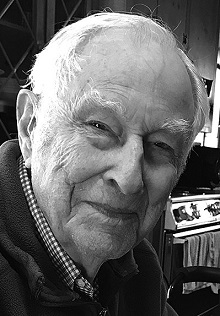

Milton Hildebrand

Professor Emeritus of Zoology

Milton Hildebrand was very much his father’s son.

Milton’s father was the legendary Joel Hildebrand, Professor of Chemistry at Berkeley from 1913 to his retirement in 1952, for whom the chemistry building on that campus is named. For good reason: he was an extremely distinguished and creative physical chemist who won virtually every award in his field short of the Nobel Prize. But he was equally committed to teaching, declaring at the age of 99 that “good teaching is primarily an art, and can neither be defined nor standardized….good teachers are born and made; neither part of the process can be omitted.” And he was equally committed to the great outdoors. As a member of the first generation of Americans to follow John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt into the wilderness for recreation and enlightenment, he managed the 1936 Olympic ski team and served as President of the Sierra Club from 1937 through 1940. He imparted all these values to his son Milton, who went on to embody them throughout his long life.

Milton grew up skiing and backpacking from age 8. At 11 he was shipped off to a boys’ school in Switzerland to learn mountaineering skills and become fluent in German. As a Berkeley student he was captain of the ski team. With his brothers and friends he made 76 ascents of Sierran peaks above 11,000’ and countless backpack trips. He became the manager for Sierra Club two-week pack trips to the high country. All these experiences were to serve him well in World War II. He was drafted into the legendary Tenth Mountain Division. After basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, he became an instructor in advanced mountaineering skills. Those skills helped him organize supply chains to the troops in the Alps, earning him a Bronze Star. In April 1945, after bitter fighting under very difficult conditions, his unit was the first to cross the crest and descend to the Po Valley, liberating Italy to the wild cheers of the populace.

Milton had married his sweetheart, Viola “Vi” Memmler, whom he had met back at Berkeley in a botany course. After demobilization he set about completing his doctorate—his thesis was on the skeletal anatomy of the dog family, Canidae. He had begun collecting skulls and skeletons as a kid and became a skillful preparator and curator of vertebrate skeletons, which informed both his research and his teaching. (His collection of some 2000 prepared specimens was donated to Berkeley at his retirement in 1986.) He was interested in both functional morphology and the evolutionary/phylogenetic aspects of vertebrate structure. At Davis, where he joined the fledgling Zoology Department in 1948, he developed and taught a two-term course embracing both approaches. The textbook he wrote for that course, “Analysis of Vertebrate Structure” – illustrated by Vi, who was an artist—went through five editions and is regarded as a classic. Milton’s teaching career ended just as vertebrate phylogeny—like so much of biology—was being revolutionized by the development of cladistics on one hand and of molecular genetics on the other. His book, then, stands as a monument to the classic anatomical approach that goes straight back to Baron Georges Cuvier.

At Davis Milton taught embryology for 19 years and his morphology courses for 34 years. But as a teacher he is perhaps best remembered for his lower-division course in human sexuality, taken by some 17,500 students over 14 years. It was a first of its kind in the University of California system, soon to be emulated by Professor Eric (“Ted”) Pengelley at Riverside. The Zoology Department at Davis declined to list Milton’s “sex course” as a departmental offering, and it came to be listed in the General Catalog as Human Development 12. Milton and Vi were accredited sex and family therapists, having received training at the Masters and Johnson Institute. Despite the topical overlap of their courses, Milton and Ted Pengelley were extremely different people with radically different lecture styles. Pengelley was loud and brusque and loved to play provocateur. Milton was reserved, calm and perpetually avuncular. Both approaches worked very well; both courses were immensely popular with students and won teaching awards. Milton received the Golden Apple Award from the Associated Students at Davis in 1967 and the first Academic Senate Distinguished Teaching Award in 1973. His interest in teaching led him to joint authorship of a much-cited study, “Evaluating University Teaching,” by the Center for Research and Development in Higher Education. It also led him to force his departmental colleagues to devote more time and energy to discussions of the subject than they perhaps wanted to! He was concerned that new Ph.D.s were dumped on the university job market with no formal training in pedagogy, and to remedy that he initiated and led a graduate course in “The Effective Teaching of Biology.”

Both Milton and Vi were by nature reserved people. Although he could have told many war stories, Milton almost never did. Even when he was honored at his 100th birthday for his heroic service in World War II, he protested that too much was being made of it. He was aware that younger colleagues viewed his approach to human sexuality as just a bit “square,” but he knew it was very effective and if he minded the occasional snickers, he never let it show. He took in good spirits the ribbing he got in skits at departmental Christmas parties as “Professor Hilton Mouldybread.” He remained physically active to nearly the end of his life, taking constitutionals daily around his north-central Davis neighborhood. He died at 102. Joel had lived to 101-1/2. He was indeed his father’s son.

Arthur M. Shapiro

Robert D. Grey

Carol A. Erickson

Judy A. Stamps