Mark Rubinstein

Professor of Finance, Emeritus

Mark Rubinstein, a professor of finance and a former president of the American Finance Association, whose ideas had a profound impact both on academic research and on Wall Street practice, died May 9th in Tiburon, CA, at age 74. Raised in Seattle, Rubinstein completed high school at the Lakeside School and received a B.A. from Harvard, an M.B.A. from Stanford, and a Ph.D. in finance from UCLA. In 1972, he joined the business school at the University of California, Berkeley (now the Haas School of Business), where he spent his entire career. A pioneer in applying mathematical tools to financial markets, Rubinstein rose rapidly through the academic ranks, interrupted only by a three-month hiatus learning the ropes as an options market-maker on the floor of the Pacific Stock Exchange.

Rubinstein’s early academic research focused on asset pricing in financial markets, showing that a financial market with diverse investors could usefully be modeled “as if” it had a single investor with average expectations and aversion to risk. This greatly simplified the analysis of complex markets. He extended William Sharpe’s Nobel-prize winning work on securities’ “alphas” and “betas” (part of today’s financial markets lexicon), going beyond simple mean-variance modeling to include more realistic investment preferences and return distributions.

Soon after the revolutionary Black-Scholes option pricing model was introduced in 1974, Rubinstein (with John Cox and Stephen Ross) developed a simplified “binomial” method for valuing a wide range of complex real-world options. The Cox-Ross-Rubinstein (CRR) model won the Chicago Board Options Exchange Pomerance Prize in 1978 and remains one of the most important valuation tools on Wall Street. His subsequent book, Options Markets (with John Cox, 1985), made option pricing theory accessible to a wider audience of students and professionals.

Rubinstein teamed up in the early 1980s with colleague Hayne Leland at Berkeley and finance professional John O’Brien to form Leland O’Brien Rubinstein Inc. (LOR). The firm provided pension and other investment funds with “portfolio insurance,” a risk-hedging algorithm for limiting portfolio losses. The algorithm required disciplined selling of stocks (or index futures) as values declined to protect, at a cost, against losses beyond a pre-specified amount. LOR’s business increased rapidly, and portfolio insurance covered an estimated $100 billion of assets by mid-1987 (roughly $1 trillion at today’s stock price levels). In 1987, Rubinstein and his two associates were three of the twelve people named Fortune’s “Businessmen of the Year.”

The stock market reached a peak in the summer of 1987, followed by an increasingly rapid decline in the fall. The required selling by portfolio insurance became more pronounced, and reached a climax on October 19, 1987, when market liquidity broke down under the heavy volume of trading. The subsequent Brady Report (1988) isolated portfolio insurance selling as a major accelerant, though not the initial cause, of the crash. These events and the role of LOR are recounted in Diana Henriques’ A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History.

In an effort to offer protection without dynamic trading, LOR pioneered the SuperTrust, an S&P 500-based fund that traded on the American stock exchange as a single security or “basket”—the first exchange traded fund (ETF) in the United States. SuperTrust units were divisible into separate securities that provided long-term option-like returns, including loss protection. Rubinstein and Leland provided the economic arguments that convinced the U. S. Securities and Exchange Commission to give LOR the first exemption to rules in the 1940 Investment Act that had prevented ETFs. These exemptions later became standard as ETFs proliferated, and they helped form the regulatory framework for what has arguably become the most important financial innovation in the last quarter century. ETF assets now exceed $6 trillion globally.

Rubinstein continued his academic research and mentoring of doctoral students at Berkeley throughout this period. He was elected president of the American Finance Association in 1993. His presidential address introduced a novel way to deduce the risk-adjusted probability distributions of future asset returns from option prices. Known as the method of “implied binomial trees,” it has since been widely used in derivatives analytics. His early 1990s work on so-called “exotic” derivatives remains a standard reference for financial “quants.” In 1995, Rubinstein was selected the IAFE/SunGard Financial Engineer of the Year, and in 2001, he helped to found the Haas School’s Master of Financial Engineering degree program. This was the first MFE program in a U.S. business school and continues to be ranked #1 by many rating services. MFE Program Executive Director Linda Kreitzman called Rubinstein “a giant in his field. He had a huge impact on our students’ lives and also our alumni. He was a brilliant, kind person and he’ll be deeply missed.” Of all his awards, the one he cherished most was the Cheit teaching award at Haas in 2003.

Although Rubinstein maintained loyalty to the concept that financial markets are in most cases informationally efficient, he nonetheless encouraged Berkeley students to examine the new field of behavioral finance. He is remembered for a classic 1999 debate on behavioral vs. rational financial markets with Richard Thaler, who subsequently won the Nobel Prize in economics (the debate was termed a draw!).

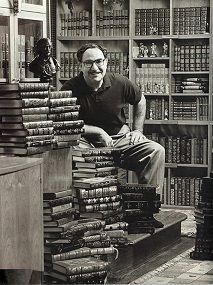

An avid student of intellectual history, with deep side interests spanning Shakespeare and early Christianity, Rubinstein created a landmark examination of financial ideas in A History of the Theory of Investments: My Annotated Bibliography (2006). It traces the development and interactions of ideas, some dating from the thirteenth century, that have culminated in modern theories of investment. With the diligence of Sherlock Holmes (of whom he was a great fan), Rubinstein shows that many theoretical discoveries were in fact misattributed. The book also provides a readable and concise synthesis of the current state of financial thought. It is a testament to his fascination with seminal ideas and the rigor that he brought to all his work.

Mark was a serious collector of books and of Chihuly glass from his native Seattle. A singular oddity was his love of Diet Coke, which he ordered even in 3-star restaurants, often to his friends’ astonishment. He is dearly missed by his wife, Diane, and children, Judd and Maisie Rubinstein.

Hayne E. Leland

2020