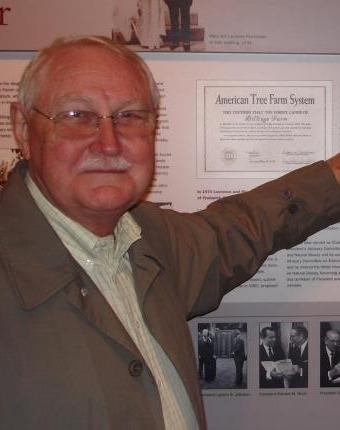

Leonard Wilkie Johnson

Professor Emeritus of French

Professor Leonard Wilkie Johnson died on September 26, 2023, at the age of 92. Johnson taught for 34 years in the Berkeley French Department. After his retirement, in 1994, he served as Professor of the Graduate School for several years, continuing to work with students in a variety of capacities.

Johnson was a pillar of the Department's culture, a standout teacher, an innovative scholar, a servant to the profession, and a model of generosity and civility to colleagues and students. He is survived by his nephew Adham, Adham's wife Crystal and their two sons Tasman and Atlas, his nephew Raef, and his brother-in-law Wafik.

Johnson was born in Oakland and raised on both the West and East Coasts, as his family moved frequently for his father's job working for NOAA. He graduated summa cum laude from Dartmouth in 1953, and then took his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1962. Along the way he studied in Florence, Aix-en-Provence, on a Fulbright, and at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, in Paris. Johnson joined the Berkeley French Department as an Instructor in 1961 and remained until his retirement as Professor in 1994. In 1989 he received the Gilbert Chinard Literary Prize of the French Institute in Washington, D.C. That same year, he was recognized by the French government with the prestigious Palmes Académiques, for his contributions to French culture, and to Franco-American cultural understanding.

Johnson was noted for his effective and popular teaching, especially at the undergraduate level. His field of specialization was early modern France, and he delighted in teaching courses on material unfamiliar to Berkeley undergraduates—inspiring, challenging, and amusing them with his mastery of the difficult language and culture of the Ancien Régime. His teaching was marked by innovative use of multi-media documents and an interest in the study of literature as a "cultural practice," long before the term "cultural studies" was popular. He was also a mainstay in the teaching of writing in the Department, and taught on occasion outside the regular campus, through the University Extension program.

Few scholars could match Johnson's wide and deep reading in the canon of French literature, and his intellectual restlessness was reflected in his scholarship. An early book, coming out of his Harvard thesis, placed the challenging philosophy of Renaissance Neo-Platonism in dialogue with the rise of the pastoral novel in the early seventeenth century, focusing on Honoré d'Urfé's massive romance, the Astrée. Though the book was completed and submitted to the UC Press, Johnson eventually became impatient with the bureaucracy of the Press, and, after additional work at revision, turned his focus elsewhere. He reinvented himself as a scholar of the late Middle Ages, steeping himself in the difficult language and complex poetic traditions of fifteenth-century French poetry—an area that is still understudied because of its difficulty and inaccessibility for modern readers. Johnson's work, however, resulted in a ground-breaking study of the field, titled Poets as Players (Stanford, 1989). The book studied the intersection of the idea of "play" as a form of literary variation, within the traditions of rhetorical composition and the entertainments of late medieval court society.

Johnson's service to the French Department was consistent and important. He served as Vice-Chair multiple times, as Acting Chair, and as Head Graduate Advisor. He was several times involved in reshaping the graduate programs and worked with students returning from EAP study. For the Faculty Senate he served on the Committee on Educational Policy (1985-91), on the Library Committee (1984-87), on University Welfare (1985-86), on COCI (1974-75, 1994-95), on the Grad Council (1974-77), and as an evaluator for the Regents and Chancellors Scholarships. In addition, he was active on the Council on Ethnic Studies (1986-89), and, in 1991-92, he chaired the committee on Curricula for the Ethnic Studies Department.

Equally impressive was his service to the profession, where he made important contributions in the field of foreign language pedagogy. He worked with the Educational Testing Service for fifteen years, ending up as Chief Reader for their Advanced Placement Exam in the 1980s. He regularly organized workshops for AP language teachers and served on the Executive Committee of the Foreign Language Association of America. He was thus an important bridge between Berkeley's language and literature departments and our colleagues across the country.

Integral to Len Johnson's interest in French culture and literature was his mastery of the food and wine of France. As active member of the Arts Club on campus he was greatly appreciated as a genial host and fabulous cook. His "punch"—a libation specially prepared for departmental parties—was known to be lethal. Towards the end of his career he developed these interests into courses on "Food and French Literature" which were widely appreciated by students.

Anyone who knew or worked with Len knew as well of his deep commitment to his spiritual life, through worship and service at Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church in Berkeley. He was very active in church life, both locally and regionally, and was eventually elected President of the Alameda Deanery.

Len Johnson's long and rich career at Berkeley spanned a time of massive upheaval, both socially and intellectually. He began his teaching career in the cauldron of the Free Speech Movement days (and regaled friends with tales of having his classes regularly interrupted by protests, as he tried to teach the Renaissance sonnet). He came of professional age at a time when the Department itself was going through a rocky patch administratively, resulting in it being placed in receivership at one point. That was followed, in the 1970s and 80s, by the importation of new types of "theory" from France, leading to a transformation in the very idea of what it meant to study literature, to be educated, to practice the humanities. Through this change and disruption, through revolution and shifting trends, Len Johnson was a calm and wise colleague, deeply committed to education, unstinting in his high standards and admired by both colleagues and students. He was a rare presence, the like of which we shall probably not see again. His passing dims the light of Berkeley.

Timothy Hampton

Nicholas Paige