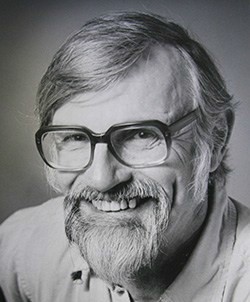

John G. Hurst

Professor of the Graduate School of Education

In May 2016, shortly after Professor Emeritus John Hurst passed away, a group of his family and friends, including students and colleagues, gathered in a circle, as equals, to share what they remembered and appreciated about him. In many ways, that gathering reflected a quality that ran through John’s life and work as an educator for well over half a century. It brought together people who were quite diverse, but who nonetheless shared a common commitment to working with others to clarify the ideals of democracy and justice, and to act upon them in their daily lives.

With that sort of commitment of his own, John was instrumental in developing a number of important educational initiatives in the Graduate School of Education, on the University of California, Berkeley campus, and in other communities to which he belonged. At Berkeley, those initiatives included: a legendary course on Democracy and Education (ED 190); the Undergraduate Minor in Education, which received an Educational Initiatives Award from Berkeley; the major in Conservation and Resources; the UC Service-Learning Program, which received a Chancellor’s Community Service Award; the program that came to be known as DeCal (Democratic Education at Cal), which has supported student-initiated courses; the Peace and Conflict Studies Program; and the Center for Popular Education and Participatory Research.

These initiatives were both innovative and, at times, controversial. They transcended the boundaries of traditional courses taught didactically by authorities who intend to give students a foundation in a particular discipline that they can draw upon sometime in the future. Instead, they brought disciplines together to address critical social and environmental issues of our times, and they empowered students to learn from and witheach other, to propose their own courses of study, to evaluate their own learning, and to apply it in very immediate ways. John’s approach to education in these initiatives was heavily influenced by work in “popular education,” particularly the work of Miles Horton, a founder of the Highlander Center in Tennessee.

While some members of the Berkeley faculty had serious reservations about John’s approach, at least to begin with, his initiatives have persisted and flourished, and the positive impacts they have had on thousands of students over the years are undeniable. To give but one example of John’s widespread and sustained impact, a graduate student working with him won a Chancellor’s Award for Civic Engagement when undergraduates she taught founded a national nonprofit organization that has supported progressive professional development for hundreds of public school teachers. Another former graduate student has noted John’s patience and persistence as an advisor, both on campus and in other venues. The theme running throughout all of this work is an approach to education that empowers people to pursue progressive social change in ways that they choose, coupled with careful, critical feedback on their efforts.

Away from Berkeley, John was an avid outdoorsman and environmentalist. He particularly enjoyed canoeing and rafting on white-water rivers in wilderness areas around the world, and he was involved in promoting similar experiences for young people, for example as a founding instructor and program developer for the Outward Bound Schools of America, and for the National Outdoor Leadership School.

John Hurst received his doctorate in psychology from Ohio State University in 1958 and, after three years as an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development, he joined the faculty in Education at Berkeley in 1961. John began his career as a conventional quantitative researcher in educational psychology, but then had the courage to do what he thought was right, given what he saw as critical social needs, and given the opportunities he had as an educator at Berkeley. For him, that meant empowering others to do what they thought was right and necessary to promote democracy and social justice. The result was a legacy that will go on living across generations.

Paul Ammon

David Stern

With contributions from Amalia Aboitiz, Paula Argentieri, and Kara Sammet

2017