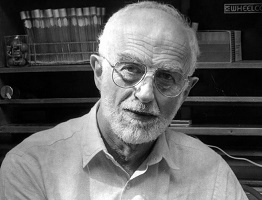

Harry Rubin

Professor of Molecular and Cell Biology, Emeritus

Harry Rubin, professor emeritus of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, died on Sunday, Feb. 2, 2020, at the age of 93. During his long career at Berkeley he was a leader in research on the process of cell transformation and on viruses that cause cancer, research that ultimately led to the discovery of cancer-causing genes called oncogenes.

Harry Rubin was born in New York City on June 23, 1926; his parents, first cousins, were Jewish immigrants from the province of Minsk in Belorussia (Belarus). His father ran a grocery store and delicatessen in Manhattan, where as a child Harry worked in his spare time. Rebelling against family expectations, he harbored the ambition to one day become a farmer. So, at age 16, he worked on a farm in upstate New York, and then, after a semester at the University of New Hampshire, enrolled in the veterinary school at Cornell University; there, still rebelling against family expectations, he joined the Cornell football team, where he served as a blocking guard. Upon graduation in 1947 with a D.V.M. degree, he went to Mexico to help with an outbreak of hoof-and-mouth disease; this was an exciting adventure because the cattle owners resisted having their sick animals culled, and military protection was required. He then joined the U.S. Public Health Service in Montgomery, Alabama, to work on viruses that can cause zoonotic diseases in humans, including rabies and Eastern equine encephalitis. In a 1991 profile in California Monthly magazine, he referred to this period working in the field as time spent “chasing cows and horses in Mexico and Louisiana." It was while working in Alabama that he met and married Dorothy Shuster, then training to be a flight evacuation nurse for soldiers wounded in the Korean war. Their marriage lasted for 68 years, until Harry's death in 2020.

Seeking new challenges, he enrolled at New York University and, a year later, in 1952, Nobel Prize winner Wendell Stanley recruited him to work in his Virus Laboratory at UC Berkeley. But studying the virus that Stanley had isolated, tobacco mosaic virus, did not appeal to him, as he was interested in studying viruses that caused animal or human disease. So, in 1953, he moved to the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena to work in the laboratory of Renato Dulbecco, where he decided to study the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), a virus discovered by Peyton Rous in 1911 that caused cancer in chickens. At that time, tumor viruses seemed to offer a tractable approach to an understanding of cancer, because they are genetically so much simpler than the host cell. In 1955 he made the seminal observation that every cell in an RSV-induced tumor was capable of releasing the virus. This observation had two implications: it indicated that the virus was permanently associated with the host cell, perhaps in the same way that a lysogenic phage is associated with the host bacterium; and it suggested that the virus played a direct and continuing role in perpetuating the cell in its malignant state.

Rubin realized that in order to study the mechanism of malignant transformation, an in vitro (cell culture) assay would be needed. Working with a graduate student, Howard Temin, he developed a focus assay, using cultured fibroblast cells from chicken embryos, to quantitatively measure the amount of infectious virus. This assay, which was published by Temin and Rubin in 1958, was of enormous significance, because it opened the way for quantitative studies of the mechanism by which RSV transforms normal cells into cancerous cells. The impact of this work (the AP reported it as "cancer in a test tube") resulted in his recruitment back to UC Berkeley in 1958 to rejoin the Virus Laboratory. There he continued work on RSV and related viruses, known as avian leukosis viruses, which resembled RSV but could not induce sarcomas in chickens or transform cultured fibroblasts. He found that these leukosis viruses could congenitally infect chicken eggs. Then, working with one of his first postdoctoral fellows, Peter Vogt, he showed that a leukosis virus was present in the strain of RSV that they were using. Furthermore, he and another postdoctoral fellow, Hidesaburo (Saburo) Hanafusa, showed that this strain of RSV was a replication-defective virus that could transform normal cells into cancer cells but required the leukosis virus — acting as a “helper virus” — to replicate and spread. In other words, the RSV could transform but not replicate itself, while the helper virus could replicate but not transform. This was one of the very first observations to suggest that the virus might carry genetic information for cell transformation and tumorigenesis that was separate from the information needed for the replication cycle of the virus.

Rubin’s work on RSV earned him the Lasker Award in 1964. "The work of Drs. Rubin and Dulbecco proves that cells can carry for many generations a foreign nucleic acid, whether RNA or DNA, that is responsible for the malignant properties of these cells,” the Lasker Foundation wrote in giving them the award in clinical research. He also received the 1961 Eli Lilly Award in Bacteriology and Immunology and the 1963 Merck Research Award for his work on RSV, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1978.

In 1970 a viral gene that is responsible for cancerous transformation, now known as viral src or v-src, was identified through a number of genetic and biochemical studies on RSV carried out by the writer, then a postdoctoral fellow in Harry's lab, Peter Vogt at the University of Washington in Seattle, and Peter Duesberg, a colleague of Harry's in the Virus Laboratory at UC Berkeley. This allowed Harold Varmus and Michael Bishop of UC San Francisco to identify an analogous gene in the cellular genome — a gene that had been captured by the Rous sarcoma virus. Called cellular src or c-src, it was the first known proto-oncogene, that is, a normal gene that when mutated can trigger cancer. Many more have been discovered since then. The discovery won Bishop and Varmus the 1979 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Thus, the ultimate significance of Harry's work on the Rous sarcoma virus is that it led to the work on cellular genes that can cause cancer; the idea that, by studying the virus one could get an insight into the cellular and genetic mechanism of carcinogenesis, had been vindicated.

Not only was Rubin's work a seminal influence in the field, but he trained many of the figures who played key roles in the study of viral and cellular oncogenes, most notably the two postdoctoral fellows already mentioned, Peter Vogt and Saburo Hanafusa. Peter Vogt subsequently wrote of the training he received in the Rubin lab that "Rubin’s style of doing research was sharply analytical, tightly data focused, and highly disciplined. Working side by side with Harry Rubin shaped me as a researcher and left a deep imprint. It was the most important formative experience in my development as a scientist." Trainees in the Rubin lab then seeded knowledge of RSV to other laboratories, and it is fair to say that the modern phase of RSV biology owes its origin to the work of Harry's laboratory.

Although Harry’s research had set the stage for the discovery of oncogenes, he – still exhibiting the same contrarian tendencies he had evinced as a youth – decided that he did not need to participate in the rush to discover new oncogenes and how they function. He wanted to move in a new direction, and by the early 1970s had switched his focus from viruses to the biology of transformed cells, examining the mechanisms of growth control and in particular the role of inorganic ions in cellular regulation. In later years, he studied the origin of spontaneous or carcinogen-induced transformation of animal cells in culture, using this system as a model for tumor progression. The finding that transformation was dependent on growth conditions and could be reversed under appropriate conditions led him to argue that it resulted from selection of epigenetic variants. This in turn led him to endorse the holistic or systems theory of cellular organization developed by the physicist Walter Elsasser, and the two of them enjoyed an extensive correspondence before Elsasser's death in 1991; the posthumous republication of Elsasser's Reflections on a Theory of Organisms included a new foreword written by Harry. He retired in 2001, but remained active as an emeritus professor, writing many articles that placed his earlier research in a broader context.

Harry had many interests outside of science. During the 1960s he was heavily involved in the anti-Vietnam war movement on campus. Then in the 1970s his interest in the Judaism he had more or less abandoned as a young man was rekindled, and he and Dorothy became members of Congregation Beth Israel in Berkeley. He was especially interested in Jewish ethics and philosophy, particularly the ideas of philosophers working in the traditions of existentialism and phenomenology such as Emmanuel Levinas, Franz Rosenzweig, Joseph Soloveitchik and Eliezer Berkovits. Harry and a group of other members of the congregation – a group that became known as the Levinas group – enjoyed meeting regularly to discuss the work of these thinkers. He remained active in the congregation and this discussion group for the rest of his life.

Harry Rubin is survived by his wife, Dorothy, and three children, Andrew, Janet and Clinton Rubin; another daughter, Nell, died in 1994. He is also survived by six grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

G. Steven Martin

2021