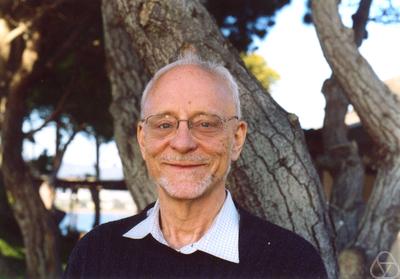

Elwyn Ralph Berlekamp

Professor of Mathematics and EECS, Emeritus

Elwyn Berlekamp was born on September 6, 1940, in Dover, Ohio, to a minister and a church librarian. He became interested in the pencil and paper game Dots and Boxes at the age of 6, but plateaued in junior high. He co-wrote the first computer chess program as a freshman at MIT in 1959, and was a Putnam fellow there. Mathematics and games remained intertwined throughout his life.

He received his PhD in 1964 from MIT and came to UC Berkeley as an Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering; he left for Bell Labs in 1967 and returned to Berkeley in 1971 as a Professor of Mathematics and Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences (EECS), a position he held until his retirement in 2002 (half-time since 1983). Berlekamp’s most famous achievement was the development of efficient algorithms for decoding “algebraic” error correcting codes, which are methods of transmitting information accurately across a noisy channel. Shannon had proved the existence of such codes with low redundancy, but no one knew how to find one which could be efficiently decoded. Berlekamp showed that Reed-Solomon codes admit an elegant and fast decoding algorithm based on elementary number theory. He complemented this with a fundamental advance in computer algebra – a fast algorithm for factoring a polynomial over a finite field. Based on his graduate course on coding theory at Berkeley in the mid-60s, he wrote a 500-page textbook, which is still a standard reference in the field.

Berlekamp was an engineer as well as a mathematician. The preface to his book contains the sentence: “There is frequently a conflict between proofs which some people consider conceptually simple and proofs which lead to simple instrumentation.” He was bothered by suboptimal implementations of his codes, so he co-founded the company Cyclotomics in 1972 to get the details right. The bit-serial decoders developed by this company became the standard used by NASA in deep space communications; they were used by Voyager II and by the Hubble Space Telescope, in particular, to transmit the iconic pictures of Neptune in 1989 and of the Eagle Nebula in 1995. They were also employed in the CD-ROM standard and continue to be used widely. For these achievements, Berlekamp was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1977 at the age of 37, its youngest ever member.

Berlekamp’s second major research interest was combinatorial game theory – the mathematical study of “games of no chance” such as Go, Chess, and Nim, and their winning strategies. A central theme was proving decomposition theorems, which relate the value of a game to the values of subgames. With Conway and Guy, Berlekamp published the four-volume “Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays” in 1982, which unapologetically blurred the lines between research and recreational mathematics and became the definitive work on the subject. The books contain hundreds of playful illustrations and at least fifty-nine hidden private jokes between the authors. Not having forgotten his childhood interest, Berlekamp wrote “The Dots and Boxes Game” in 2000. He commented that “[the] game is remarkable in that it can be played on at least four different levels. Players at any level consistently beat players at lower levels, and do so because they understand a theorem which less sophisticated players have not yet discovered.”

After selling Cyclotomics to Kodak in 1985, Berlekamp became interested in finance despite Claude Shannon’s unambiguous advice to him as an undergraduate (“Do not invest in the markets.”). At the suggestion of his friend and fellow mathematician Jim Simons, he bought a controlling share in Axcom, a struggling hedge fund, in 1989. Over a six-month period he redesigned its algorithms to exploit subtle market fluctuations that occur on short time scales (which they referred to as “ghosts”) leading to a 55% net return in 1990. Berlekamp promptly sold his share back to Simons and returned to teaching at Cal. The “Medallion” fund became and continues to be the most successful hedge fund in the world, and the style of algorithmic trading it pioneered remains highly influential.

Beyond his accomplishments in mathematics, engineering, and business, Berlekamp was extraordinary in his service to the university and to society. He was chair of the EECS department from 1975 to 1977. He was a key supporter of the establishment of the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI) in the 1970s and served as its chair from 1994 to 1998; his fundraising efforts during that period were crucial to ensuring its long-term viability. The Berlekamp Postdoctoral Fellowship was established at MSRI in 2014 by devoted colleagues and friends and the Elwyn and Jennifer Berlekamp Garden is also there. He co-founded the Gathering 4 Gardner foundation, which holds yearly conferences featuring mathematicians, magicians, artists, and others, with the goal of popularizing and developing recreational mathematics in the spirit of Martin Gardner. In K-12 education, he helped finance the Berkeley Math Circle in the 1970s and more recently, he and his wife co-founded the Elwyn & Jennifer Berlekamp Foundation in Oakland, which characteristically “is devoted to furthering the mathematical sciences, from the most advanced research to the playful and inspired inventions of amateurs.” In all, he served on over 45 boards of various organizations. He supervised 14 doctoral students and had a total of 42 mathematical descendants.

Berlekamp won many awards in addition to those mentioned above, including the Centennial Medal, the Kobayashi Award, the Hamming Medal, and the Shannon Award, all from the IEEE. He won a Technical Oscar from the Motion Picture Academy in 1995 for “Cinema Digital Sound” and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1999.

Berlekamp was an expert juggler, unicyclist, and Go player. He was a regular at the Berkeley Go club. An opponent there commented that his play would slow down as he approached the endgame and transitioned from intuition to combinatorial game theory calculations.

Professor Emeritus Richard Karp said of Berlekamp: “He was a brilliant person who was always effective in everything he tried to do, whether it was mathematics or game theory or consulting and investment. He had a curious and powerful mind.”

Elwyn Berlekamp died on April 9, 2019 at his home in Piedmont, CA, of pulmonary fibrosis. He is survived by his wife Jennifer, and three children, Persis, Bronwen, and David.

Nikhil Srivastava

2021