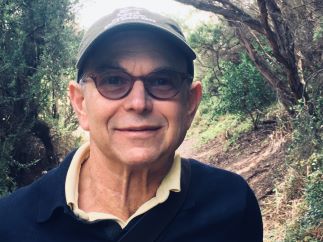

David Lieberman

Professor of Law, Emeritus

David Lieberman was born in Canton, Ohio on May 21, 1953, to George and Sylvia Lieberman, and was raised in Rockville Center, New York. He completed high school in England when his parents took a sabbatical there, and stayed on to attend the University of Cambridge, where he took undergraduate and graduate degrees. He received his PhD in History from the University of London in 1980. After returning to Cambridge as a teaching fellow, he was then recruited by UC Berkeley Law School’s still-new interdisciplinary Jurisprudence & Social Policy Program in 1984, as its historian of legal and social thought. Until his retirement in 2022, just before his untimely death, David was a mainstay of the Program, serving as its head, and advising countless students. In his undergraduate seminars and lectures, notably his courses on social theory and the history of punishment, and through his mentorship, David also touched the lives of countless students, especially those among the first in their families to attend university. He was deeply committed to the ideal of a great public university, and its role in the lives of all California’s residents.

David was, for all who knew him, a mensch: a rock of good judgment, a source of comfort, love, generosity, kindness, and wit. In both his professional and personal life, he combined an unerring instinct for the right with an insightful, compassionate and tactful approach to the people involved. Almost every encounter with him was leavened by his sense of humor, which, when fully deployed, could reduce even the most staid of audiences to helpless laughter. A globally respected historian, David focused his scholarly lens on the history of legal, political, and social thought, especially in 18th century England, particularly the works of the prolific polymath, Jeremy Bentham.

David was part of the new generation of Bentham scholars, whose comprehensive knowledge of the broader intellectual context of the 18th century enabled them to identify the significance of Bentham’s prodigious work as it appeared at the time, and not just through the retrospective lens of modernity. Phillip Schofield, Professor of History at University College, London and Director of the Bentham Project, whose mission is putting into print the voluminous manuscripts left by Bentham, said of David’s work that it “displays not merely exceptional scholarship, but it is characterized by an elegance of style and clarity of expression that Bentham himself recommended, but in the eyes of many did not often achieve.”

David had a particular genius for the memorable scholarly phrase, to wit: “Hitherto we have been so devoted to finding behind Bentham’s legislative theory a nation of shopkeepers, that we have neglected his commitments to a nation of newspaper readers.” As Simon Devereaux, a fellow 18th century historian at the University of Victoria, said, “Few scholars have been so ill-assorted as David Lieberman and Jeremy Bentham. The late John Beattie once jokingly remarked to me that the Bentham Project had to keep hiring new editors for each volume of the great man’s correspondence because no one who had spent a year or two in Bentham’s company could bear the prospect of any more! So vast were David's gifts of sympathetic analysis and crystalline prose, however, that one always comes away from his work—The Province of Legislation Determined (Cambridge, 1989) remains pathbreaking and unrivaled—feeling as though the effort to climb Mount Jeremy might be worth it.”

While David took pride in his scholarship, he gave, if anything, even more of himself in his teaching and mentoring. This was especially true for young colleagues, who could count on his humor and good sense, of course, as both a model of how to muddle through academic triumphs and travails, and a source of specific advice on both their scholarship and their careers. Karen Tani, a former Law colleague, now University Professor of History and Law at the University of Pennsylvania, said that she learned from David “about how you treat people who have less power, who are newcomers, or who feel vulnerable. From the time I was a baby professor, very unsure myself, David treated me like I had value—indeed, like I was a jewel in the UC Berkeley crown. He asked my opinion about important matters. He invited me to dream with him about how to make Berkeley better.”

David was an equally supportive colleague for those at the other end of their careers, whom he continued to visit and care for. His retired longtime colleague, Harry Scheiber, said that during the sixty years of his career, “I have never met someone with more integrity and kindness than David. Apart from his brilliance, he was dedicated to his institution and friends.” Harry noted in particular that during the pandemic, David would make chicken soup and bring it to Harry and his late wife, Jane. Another longtime Law colleague and friend, Stephen Bundy, captured the essence of David’s spirit: “Because of who he was, and how he saw and treated others, David made everything better: good experiences became more enlightening, rewarding and joyful; bad experiences, less painful or destructive.”

David’s care for the people at Berkeley was matched by his care for the institution itself. Apart from his roles in leadership positions in the Law School, he served on the campus Budget Committee from 2007-2009, and as its chair in 2010. Perhaps his most significant campus service was as the chair of the Graduate Division Task Force on Jewish Studies, a task that called for every ounce of diplomacy and institutional intelligence he possessed. The Berkeley Faculty Senate recognized his success in that delicate task with the Faculty Service Award in 2017; the Law School’s Lifetime Faculty Achievement Award followed in 2019. His colleagues in JSP continue to ponder every collective issue with the question, “What would David do?”

Beyond campus, David’s passions took him across time and space, from music (especially opera) to good wine and food, to philosophy and politics, to the great outdoors. And the center of his life was his family and friends. All who had the privilege of knowing him had their own experiences of his grace. Though he himself had come through some very difficult health challenges, including a cycling accident in 2016 that threatened to paralyze him, he never indulged in self-pity. Even in his hardest moments, he was concerned for others, worried about being a burden but also able to show his gratitude for the love that was returned to him.

David died in a tragic hiking accident in Lassen National Park on Saturday, September 10, 2022, at the age of 69. He died just as he and his wife of 35 years, Carol Brownstein, were beginning their retirement, on the first of many planned travels and adventures. He leaves behind Carol; his three children, George, Hannah, and Aaron Lieberman, of whom he was enormously proud; his sisters Lynn Ritvo and Deborah Lieberman; and countless friends, colleagues, and former students, many of whom contributed moving witness to his life on the departmental memorial website.

Christopher Kutz