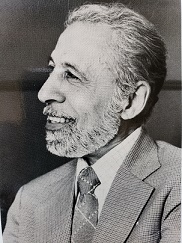

David A. Alhadeff

Professor of Business Administration, Emeritus

David Albert Alhadeff, professor emeritus in the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, died on March 15, 2011, at age 87.

David was born on March 22, 1923, and was raised in Seattle, where he graduated summa cum laude from the University of Washington. During World War II, David served as a military intelligence officer with the U.S. Army. When the war ended, the Army posted David to Japan until he left the service in August 1946.

By 1950, David had earned his Ph.D. in Economics at Harvard University and had joined the faculty of the Schools of Business Administration at UC Berkeley. He researched and taught there for the next 38 years, until his retirement in 1987. During his long and admired career, David served the Schools of Business Administration in various ways, including two tours as associate dean of academic affairs. While on the Berkeley faculty, David’s banking expertise led to his being asked to advise the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the U.S. Department of Justice, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, and the California Department of Finance. His reputation also led to his serving for a few years as an associate editor of the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking.

His first two books, Monopoly and Competition in Banking (1954) and Competition and Controls in Banking (1968), brought David widespread recognition as a banking scholar. His papers in academic journals in the intervening years cemented his academic reputation.

In Monopoly, David analyzed the sizes of banks and the rates they charged for loans through the lens of microeconomics. While that might seem natural now, from the time of the financial and legislative convulsions of the 1930s in banking until the 1950s, banks were often viewed as adrift, passively investing in as many bonds as governments issued. David argued that banks were better seen as purposeful lenders with economically-rational policies for loans and the rates they charged. As the years rolled by and bonds rolled off bank balance sheets, appreciation for David’s analysis rose as it came to be used by more and more banking economists in the two decades after its publication.

Competition was an altogether different book. In contrast to his earlier revelations of powerful economic factors in U.S. banking, David’s second book documented the very considerable extent to which both the public and the financial sectors in Italy, France, and England constrained both banks and the economic factors that would affect them. As such, his research in this book essentially showed why his analysis in Monopoly would be of limited use if applied to European banks.

Testimony to David’s inquisitive, open-minded, and rigorous approach to economics was his third book, Microeconomics and Human Behavior: Toward a New Synthesis of Economics and Psychology (1982). He wrote it late in his career, but very early in the life cycle of behavioral economics and finance. Long before coupling economics with psychology became mainstream, David’s book plumbed how much of conventional economics could be justified by established empirical findings in operant psychology. His analysis demonstrated that a surprising amount could be justified, but he also pointed out how other findings in psychology might well provide the foundations for better economic analysis. As David so often did personally with his faculty colleagues and students, to the economics profession his book offered support for what was being done—as well as encouragement, rationales, and guidance to do better.

David was a popular teacher. His caring about his students’ learning and their welfare was always evident. His smile was quick and his manner gentle. When the Haas School of Business instituted awards for outstanding teaching, David was the first recipient. Another indicator as to how his students valued David was a million dollar gift in his honor. Four decades after taking David’s banking class, James J. Lowrey, along with his wife Marianne, endowed a chair specifically for the support of teaching and of research about financial institutions from a micro-economic perspective. Recalling that David was his mentor, Mr. Lowrey credited him with providing the educational opportunities and formative experiences that underpinned his successes on Wall Street.

Upon his retirement in 1987, the Berkeley campus chose to bestow David with one of its highest honors, the Berkeley Citation. In retirement, David took up golf, partly so that he could continue his stimulating and congenial conversations with his late, fellow Business School colleagues, professors Joe Garbarino and Fred Morrissey.

David was preceded in death by his beloved Charlotte. Charlotte Pechman Alhadeff was David’s soulmate, his friend, his wife, and his coauthor. In her memory, David established the Charlotte Alhadeff Scholarship Fund at Berkeley.

David was interred next to Charlotte in the Seattle Sephardic Brotherhood Cemetery.

James A. Wilcox

2019