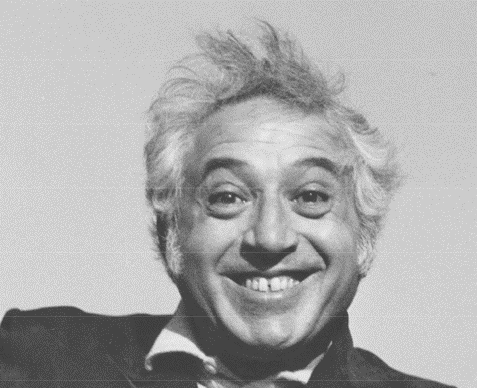

Bernard Taper

Professor of Journalism, Emeritus

Bernard Taper led an extraordinary life—a life consisting of many independent and overlapping acts. He was a determined "art detective" immediately after World War II, then an ace newspaper reporter, a gifted writer for The New Yorker magazine, an author of several important books, a force behind the California Shakespeare Festival and finally, a dedicated and beloved professor of journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, for almost three decades (from 1970 to 1998). Throughout, he was easy-going and affable, while he adhered to the most rigorous editorial standards.

He was born on January 28, 1918, in Scotland and died on October 17, 2016, in Berkeley, of a bacterial infection. He remained exceptionally vigorous until the last few years of his life. He was an avid tennis player until he was in his late 80s. He had outlived all his tennis buddies, he told me once.

Bernard spent his early years in London in an Orthodox Jewish household. When he was 11, he took a freighter alone across the Atlantic and settled in Los Angeles. He then attended Berkeley, where he majored in English but initially did not get his degree because he was too busy working on student publications. After college, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and then discharged in 1946 to become a "Monuments Man" with an art intelligence office for the Allies in Germany. As an art detective, he investigated and recovered works of art and other cultural objects looted by the Nazis. These were then returned to their right owners.

Bernard left Germany in 1948. He earned a bachelor's degree from UC Berkeley and a master's degree in creative writing from Stanford University in 1955. Throughout his career, he used many of those skills, first working as a reporter for the San FranciscoChronicle from 1950 to 1955, a period when the Chronicle excelled as an insouciant, sometimes outrageous publication that mirrored the fun-loving city in which it was published.

In the obituary of Bernard that appeared in the Chronicle, the writer Steve Rubenstein recalled one of Bernard's many memorable stories—a feature about a sold-out concert at the Cow Palace by a young pianist named Liberace. Bernard wrote: "The multitude laughed at his most casual attempt at humor and it applauded every time he gave the slightest intimation the applause would be welcome." Totally deadpan, Bernard reported on the pianist's effect on his audience: "San Mateo Deputy Sheriff Frank Martin said there were eight faintings, two epileptic fits and one convulsion."

In 1956, Bernard joined The New Yorker as a staff writer, one of the most prestigious perches in journalism. He wrote a fascinating assortment of profiles, including sketches of chess prodigy Bobby Fischer and the first prime minister of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah. In 1963, he turned a series of his profiles of choreographer George Balanchine, co- founder of the New York City Ballet, into a book, Balanchine. Many consider it to be the authoritative account of the choreographer's life. Several other books followed. His reporting on civil rights from the early 1960s, appeared in a book, Gomillion versus Lightfoot: The Tuskegee Gerrymander Case, that is still in print.

Bernard joined the faculty of Berkeley's brand-new Graduate School of Journalism in 1970, one of the first tenured professors recruited by founding dean Edwin Bayley. Year in and year out, Bernard taught a full load, including a class on writing profiles that influenced a generation of authors. Bernard continued to write profiles and books, and in the 1970s and 1980s, he nurtured the California Shakespeare Theater (now known as "Cal Shakes") as chairman of its board.

Bernard belonged to a special breed of editor/teacher. He did not edit the article so much as he edited the writer. Sara Catania spoke at a campus memorial service early in 2017 and quoted from a blog post she had written earlier, reminiscing about an article of hers that Bernard edited in 1991 when she was a 23-year-old graduate student. "The work was a mess, but Bernard saw promise," Sara wrote. "What Bernard did not do, and what a lesser editor surely would have, was rewrite the piece." She continued: "Bernard's motivating interests were good ideas and good, clear writing. They seemed to be the only things worth his time." As importantly, "he treated his students with the same respect some of his colleagues reserved for 'real' writers."

When I was dean of the journalism school in the 1990s, I had one run-in with Bernard, who was a teacher of uncommon kindness and gentleness. A few years into my deanship, I made what I figured was a nifty personnel move. But I did not get faculty buy-in first, and that was a mistake—a big mistake. When Bernard found out about this news, he took me to the woodshed—or his version of it. He asked to have coffee with me. We went for coffee down the street. We sat down, he looked at me sternly for a couple of seconds, and in his clear, soft voice, asked: "What gives?"

That is about as angry as he got, but I surely learned one of the most important lessons of being dean: Always consult your colleagues. That is a lesson that has stuck with me during my career.

Bernard's sense of humor never left him. At the campus memorial service, his longtime caregiver spoke lovingly of him and related this anecdote: When Bernard was 96, he went to his neurologist who did a memory check. First question: What day of the week was it? Bernard got that. Second question: Who is the president? Bernard got that right as well. Third question: Spell the word "world." Bernard obliged. Finally, the doctor asked him to spell "world" backwards. Without missing a beat, Bernard turned his back to the doctor and spelled "world."

He is survived by his widow Gwen Head, a poet, of Berkeley, and his son, Mark, a professor, of Bozeman, Montana.

Tom Goldstein

2017