|

|

IN MEMORIAM

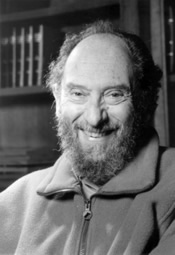

Sheldon Margen

Professor of Public Health, Emeritus

Berkeley

1919–2004

At the age of 13 he had read the works of Euclid and was arguing with his high school geometry teacher over how to solve theorems. When he was 15 he enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). By the time he was 20 he had a master’s degree in zoology and experimental embryology and four years later he graduated at the top of his medical school class from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). With a photographic memory and a passion for learning and teaching, he became an acknowledged expert in fields ranging from medicine, to nutrition, to endocrinology, to biochemistry, to statistics, to public health, to ethics and ultimately to what has become known as “wellness”. On December 18, 2004, at the age of 85, Sheldon Margen died at his home in Berkeley after a two-year battle with cancer. He treated his illness like a difficult research problem, relentlessly combing the Internet for answers that, sadly, he could not find. At the end, his acceptance of the inevitable was made all the more difficult because it meant that he had failed to find the solution he was seeking. It was something he was not used to.

Sheldon was born on May 19, 1919 in Chicago, Illinois. His parents, both Jewish immigrants from Russia, had little formal education, but were voracious readers and taught themselves English as soon as they arrived in this country. An only child, and intellectually years ahead of his peers, his childhood was often lonely. Books became his best friends and libraries his playground. A talent for playing the piano led him to consider a career in music but once he was exposed to higher levels of theory and composition he realized that his innate musical talent was not enough to carry him further down that path.

His choice to pursue medicine was more accidental than purposeful. As a graduate student at UCLA he pursued a difficult master’s project in developmental embryology and ultimately wrote a thesis that contradicted earlier work by one of his advisers. He was told to change his conclusions, but he refused. In turn, UCLA initially refused to award him the degree. Unable to pursue a doctorate without his master’s degree, he applied to medical school at the very last moment. Ultimately, President Robert Sproul intervened with the faculty at UCLA and Sheldon’s master’s degree was granted.

Sheldon met his wife Jeanne Sholtz at a piano recital when he was 15 and she was 10. They shared not only a piano teacher, but also a profound love of music. Shortly thereafter Sheldon enrolled at UCLA, but he and Jeanne remained close friends and ultimately fell in love. They were married in 1944, just before he began his army service. He was stationed in France and Germany at a time when American prisoners of war were being released. When the generals ordered steak and potatoes for the returning men, Sheldon intervened and said this would make the soldiers sick and could even kill them. Of course his warnings were ignored and the results were as he had predicted. Sheldon then became instrumental in changing the protocol to one that was more appropriate for refeeding men who had been starved for long periods of time.

When he completed his army service, Sheldon received several fellowships to pursue a career in metabolic research. Working with members of the biochemistry faculty at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) and UCSF, he was involved in early experimentation with what came to be known as cortisone and was among the first to administer this new substance to human volunteers. He also helped to set up an institute for metabolic research at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, California, and later moved it to Highland Hospital in Oakland.

In 1951 he and his longtime friend Leon Lewis established what would become a thriving medical practice in Berkeley. He also took over a failing clinical laboratory and built it into the first fully automated facility of its type in the country. Sheldon, who had never really wanted to practice medicine, ended up with a reputation as “the doctor’s doctor”. His practice, which was primarily consultative in nature, included many of the area’s doctors and their families. He took on the toughest cases, the ones nobody else could figure out. His diagnostic ability was legendary and he was credited with saving many lives during the years he was in practice.

In 1962, Sheldon was invited to join the faculty of the Department of Nutritional Sciences at UC Berkeley. Together with Doris Calloway, he established a metabolic unit, known as the penthouse, where some of the first well-controlled human nutrition research on healthy volunteers was carried out. At the time that this research began there was no federal or local oversight of human experimentation to insure that the research being carried out was safe and ethical. Along with faculty members of the School of Social Welfare and the School of Law, Sheldon helped to establish the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects to review and regulate all campus research having to do with human volunteers. This committee set standards which are still in effect today and which were the model for federal regulations that followed several years later.

Over the course of nearly 20 years, his research on protein and energy requirements and the other studies carried out in this unit provided the data that were later used to help the United States government prepare Recommended Dietary Allowances for the American Population. From 1970 to 1974, he served as chair of the Department of Nutritional Sciences. Many of his students from those years have gone on to become leaders in all areas of nutritional research and practice both here and abroad.

From 1970 to 1974, Sheldon was also heavily involved in helping to develop another innovative program on the Berkeley campus, the Health and Medical Sciences Program (now known as the Joint Medical Program). He served as its original clinical coordinator, bringing community physicians into the program to teach and advise students. He also chaired the Integration Committee, which sought to integrate social sciences and humanities into the medical curriculum.

In 1979, Sheldon transferred from the Department of Nutritional Sciences to the School of Public Health. While his primary interest remained nutrition, he began to feel that the focus was too narrow and he wanted to pursue the broader field of public health. As head of public health nutrition, he was concerned about the lack of an active doctoral program so he reorganized the unit to create one. Within the first year, 12 doctoral students enrolled. He served as the advisor to all of them.

In 1982, a publisher from New York approached Sheldon with an idea to create a national newsletter on health promotion and disease prevention in collaboration with the School of Public Health. While this idea did not initially meet with universal enthusiasm from the faculty and administration, Sheldon and his colleague Joyce Lashof (then dean of the school) persisted in getting the needed approvals and developing the plan. In October 1984 the University of California, Berkeley Wellness Letter was born. It quickly became one of the largest, most successful and most valued newsletters of its type in the country. His role in assuring the accuracy of every article was crucial to the ultimate success of the publication. He was meticulous in checking every fact, every word, and every idea. He also insisted that all the royalties received by the school be earmarked for student support. In addition to the support that is made available to current students, an endowment that he established (and which carries his name) was set up to insure perpetual student support. Now, more than 21 years later, the Wellness Letter continues to bring crucial funding and great prestige to the School of Public Health.

In 1989, at the age of 70, Sheldon officially retired from his position at UC Berkeley. However, he continued to work on the Wellness Letter and other projects close to his heart, always refusing to take the extra compensation that was available to him.

In 1990, following his retirement, outgoing Chancellor Michael Heyman asked Sheldon to head up a struggling interdisciplinary program called Peace and Conflict Studies (PACS). Suffering from internal disagreements and external instability on the campus, PACS was having a difficult time serving the needs of the students who had chosen to be a part of this innovative and challenging area of study. During the four years of his chairmanship, Sheldon struggled to resolve the problems, bring the faculty together philosophically and establish a permanent place for the program on the campus. One of his colleagues, when asked to describe Sheldon’s contribution to the PACS program, said that “Sheldon was somebody who everyone trusted and he was able to mediate the different viewpoints and personalities of the faculty and administration. He also immediately recognized that the students in PACS needed a great deal of TLC and he delivered it in the form of his endless ability to listen and hug.” He is widely credited with saving the program at a critical time in its history. PACS has gone on to become one of the biggest and most widely respected programs in its field.

Throughout his life Sheldon was an outspoken advocate for the disenfranchised and less fortunate around the world. He was an active participant in the Free Speech Movement, the antiwar movement, and dozens of other political and social causes that he felt strongly about. He devoted a great deal of his professional work to consultation and research projects that concerned malnutrition around the world. In particular, he was a consultant to the government of India and worked tirelessly on research in Guatemala, Mexico, Thailand and other parts of Asia. He was also a member of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S.–Japan Malnutrition Panel of the National Institutes of Health. He published more than 150 articles in professional journals and was the editor of several books.

In October 2004, as his health was failing, Sheldon participated in a ceremony to name the Sheldon Margen Public Health Library at UC Berkeley in his honor. The accolades and loving tributes were almost overwhelming for him. He quipped that this was probably as close as anybody could get to attending their own memorial service. Two and a half months later he was gone. Sheldon is survived by his loving wife, Jeanne, and three sons, Claude, Peter and David, and two grandsons, Cole and Jared. A fourth son, Paul, died the previous year. Those of us who knew and loved Sheldon will miss his brilliant intellect, his infinite compassion and his total willingness to listen and to hear at the deepest level. Most of all we will miss his hugs.

John E. Swartzberg

Leonard J. Duhl

Joyce C. Lashof

Dale A. Ogar