|

|

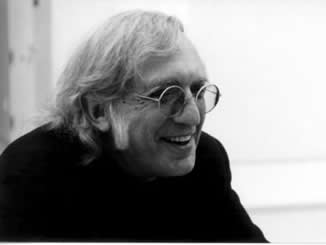

IN MEMORIAM

Lawrence W. Levine

Margaret Byrne Professor of History, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1933 – 2006

Lawrence W. Levine, an influential historian for more than three decades, died October 23, 2006, of cancer at his home in Berkeley. He was 73. Levine joined the University of California, Berkeley faculty in 1962, retiring in 1994 as the Margaret Byrne Professor of History. That same year he was appointed professor of history and cultural studies at George Mason University in Virginia.

Born on February 27, 1933, in New York City, where his father operated a fruit and vegetable stand in Washington Heights, Levine was educated in the public schools. Following graduation he enrolled in the City College of New York and then in the graduate program at Columbia University, where he completed his Ph.D. under the direction of Richard Hofstadter. When he left New York in 1961 for his first job as an instructor at Princeton University, he described it as crossing the Hudson River into America. The next year, he would enter the larger America, heading westward for California and Berkeley, where he almost immediately made his presence felt as a colleague, a teacher, and a generous mentor for his students.

Both as a teacher and as a writer, and in his active role in the profession, Levine used his wit and humor, as well as his irreverence, his combative, questioning spirit, his sometimes quiet rage, and his not so quiet rage to afflict the comfortable, unmask hypocrisy, and expose pretensions (no matter their ideological bent). He made a compelling argument for what the profession accomplished over the past several decades. The study of the past, in particular of American culture, he believed, has never been more dynamic, more exciting, or more suggestive; it has never been fuller, more varied in its focus, more open in its approaches. His own work testified to this assessment. Levine appreciated, more perceptively than most historians, the interplay of thought and behavior, and of folk and popular culture. He broadly and imaginatively defined historical documentation and historical consciousness, bridging disciplines, making full use of popular culture—film, music, folklore, humor, and oral testimony—as interpretive and cultural documents to recover the lives and agency of ordinary people, the “historically voiceless,” those men and women who expressed themselves in ways historians had seldom considered. In academia, Levine argued for a curriculum that reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of the country. In the late 1980s, he was a member of the Berkeley Division’s Special Committee on Education and Ethnicity, which developed Berkeley’s breadth requirement in American cultures, first launched in 1991.

Levine has profoundly influenced the ways in which we think about American history. His first book, Defender of the Faith (1965), a study of William J. Bryan’s final decade, revisited many of the clichéd images of Bryan and the 1920s. In it, as he came to realize, he was seeking “to understand a different part of the country and a different culture than the one he knew.” Black Culture and Black Consciousness (1978), his masterpiece, broke new ground in its focus and sources and transformed the study of the black experience in slavery and freedom, fully embracing Ralph Ellison’s challenge: “Everybody wants to tell us what a Negro is. But if you would tell me who I am, at least take the trouble to discover what I have been.” Black Culture and Black Consciousness forced historians to rethink how they document the past, how they reconstruct the experiences of ordinary people. Levine expanded the definition of protest and resistance. More extensively and more imaginatively than any previous scholar, he made use of the rich oral expressive tradition of African-Americans to examine how they perceived themselves, their position in society, and their relations with whites, and the ways in which they used music, humor, folktales, religion, proverbs, toasts, and verbal games to assert their own individuality, aspirations, communal solidarity, and sense of being, enabling them to “transcend the restrictions imposed by external, and even internal, censors.” He took us into a world in which, as he wrote, “the spoken, chanted, sung, or shouted word has often been the primary form of communication.” A pathbreaking study of folk thought and culture, Black Culture and Black Consciousness has exerted an extraordinary influence on several generations of scholars—not only historians but anthropologists, folklorists, sociologists, musicologists, and students of American and African-American culture.

In Highbrow/Lowbrow (1988), as in Black Culture and Black Consciousness, Levine continued to explore new historical paths, seeking to understand the complex and varied meanings of culture, defying its traditional categorization. The work in which he collaborated with his wife, Cornelia, The People and the President: America’s Extraordinary Conversation with FDR (2002), examined President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s fireside chats and how they were perceived by listeners. It was a work that began to suggest the dimensions of Levine’s ongoing project on the culture, thought, and social fabric of American society in the 1930s and the many different ways Americans tried to give expression to what was happening around them.

What has characterized Levine’s published work is sound judgment, clarity of analysis (free of the jargon that mars so much work in cultural history), and, as in The Opening of the American Mind (1997), an acute awareness of the uses and abuses of history, a sensitivity to the varieties of historical documentation and consciousness, and a respect for the complexity and integrity of the past. He cared deeply about how we conceptualize that past, and about how we teach and communicate it.

He cared deeply, too, about the world in which we live, and what we make of this society. Throughout his life, Levine lived both his scholarship and his politics. From the very outset, he immersed himself in the political life of Berkeley – in, for example, a sleep-in in the rotunda of the state capitol in Sacramento to press for fair housing legislation, and the sit-ins in Berkeley organized by CORE to force stores to hire black people. He participated in the march from Selma to Montgomery, expressing his solidarity with the civil rights movement. During the Free Speech upheaval at Berkeley, he came to the defense of students protesting a ban on political activity on campus in support of the civil rights movement.

During his 32 years on the faculty, Levine received many honors. A champion of multiculturalism, he won a MacArthur award in 1983 for his extraordinary scholarship; two years later he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and in 1994, he was named a Guggenheim Fellow. From 1992 to 93, he served as president of the Organization of American Historians, and he received the American Historical Association’s 2005 Award for Scholarly Distinction.

Levine is survived by his wife Cornelia; stepson Alexander Pimentel of Richmond; sons Joshua and Isaac of Berkeley; sister Linda Brown of New York City; and three grandchildren, Stephanie and Benjamin Pimentel and Jonah Levine.

Leon Litwack

Robert Middlekauff

Irwin Scheiner