|

|

IN MEMORIAM

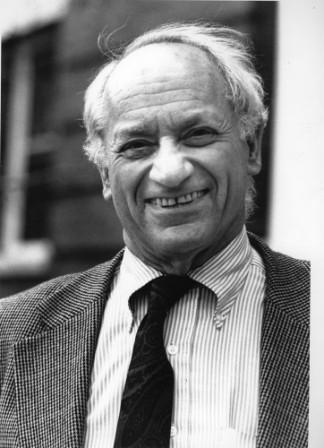

Jack Block

Professor of Psychology, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1924 – 2010

Jack Block, one of the leading personality psychologists of his generation, died on January 13, 2010, at his home in El Cerrito, California. His first publication appeared in 1951, and his most recent one is now in press. Each year in-between saw substantial contributions to the literature, many of the most important of them written in collaboration with his wife Jeanne (1923–1981), herself a distinguished developmental psychologist.

Block was born in Brooklyn, New York on April 28, 1924, the son of immigrant parents, and graduated from Brooklyn College in 1945. After receiving a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1946, he completed his graduate training at Stanford University, earning his doctorate in 1950. From 1950 to 1954, he was a research psychologist at the Langley-Porter Clinic of the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. His association with Berkeley began in 1952 with an appointment as assistant research psychologist at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (now IPSR, the Institute of Personality and Social Research). He joined the Department of Psychology as an associate professor in1957 and spent the whole of his career in the department, retiring in 1991. The honors he received during his career will give a good sense of the range of his accomplishments: Henry A. Murray Award (1985) of the Division of Personality and Social Psychology of the American Psychological Association (APA); G. Stanley Hall Award (1990) of the Division of Developmental Psychology, APA; Bruno Klopfer Award (1998) of the Society of Personality Assessment; Saul B. Sells Award (1998) for lifetime achievement of the Society of Multivariate Experimental Psychology; award (2000) from the Society of Personality and Social Psychology for distinguished contributions to personality psychology, thereafter named the Jack Block Award; award (2006) from the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development. He was, in addition, a fellow of five divisions of the APA and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Block is probably best known for the two major longitudinal studies he conducted. The first one, begun in 1960, brought new life to data collected earlier at the Institute of Human Development. This study, published in the book Lives through Time (1971), was noteworthy not only for its contributions to the understanding of stability and change in personality, but also for its inventive methodological approach. Aware of the limitations involved in the use of data collected by others, the Blocks in 1968 undertook an ambitious, multi-method longitudinal study of their own design that followed participants on a wide range of psychological and behavioral variables from nursery school through adulthood. The project generated a continuous stream of publications that consistently demonstrated a remarkable continuity between childhood and early adult personality and adaptation. The sensitivity to issues of methodology that is a strength of these studies was present in Block’s work from the outset. Indeed, his first two books, The Q-sort Method in Personality Assessment and Psychiatric Research (1961) and The Challenge of Response Sets (1965), were both psychometric in focus.

There are two other facets of Block’s career that need to be mentioned to give a complete picture of his scholarly contribution. First, he was a formidable critic, sometimes unrelenting, but not intemperate, who sought by his criticism to improve the quality of research and thinking in personality and social psychology. Most notable in this regard was his empirical and theoretical critique of the substantial group of psychologists who, in his view, speciously attacked the validity of the concept of personality. Second, much of Block’s research was informed by his theorizing about the dynamics of personality development and the intrapsychic factors that eventuate in behavior. It was, though, not until 2002 that he presented an extended and fully integrated account of his theoretical approach in his book, Personality as an Affect-Processing System.

The last time many of us saw Jack in a professional setting was during one of the weekly colloquia at IPSR, which he continued to attend as long as he was able to do so. At the end of a presentation, he would regularly ask, “Have you looked at individual differences?” That question was one he addressed in study after study; it lay at the heart of his long, productive career.

Gerald A. Mendelsohn

2010