|

|

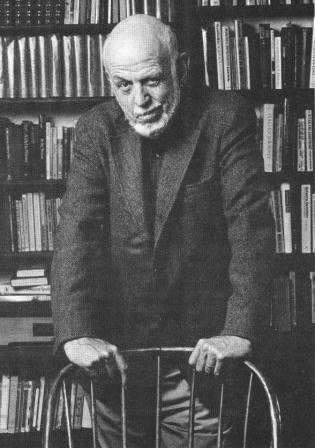

IN MEMORIAM

Henry Farnham May

Margaret Byrne Professor of American History, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1915-2012

Conscientious, brooding, resilient, Henry F. May made an indelible impression on the countless students and colleagues whose lives he touched at the University of California, Berkeley from the time he arrived in 1952 through his retirement in 1980 and even until his death at the age of 97 at his home in Oakland, on September 29, 2012.

Born in Denver, Colorado, on March 27, 1915 to a family proud if its New England ancestry, May moved as a child to Berkeley where he attended high school and then completed his undergraduate degree here at “Cal” in 1937. Among his classmates was Robert McNamara, later Secretary of Defense. May’s graduate study at Harvard was interrupted by World War II, during which he served as a Japanese translator for the United States Navy. His most striking assignment during the war, he liked to tell friends, was debriefing “Kamikaze” pilots who failed in their efforts to sink American ships while crashing their planes suicidally into them. Frightened and expecting to be summarily executed, May welcomed these Japanese men to a continued life as prisoners of war while trying to learn what he could about the bases from which they had flown. After the war May completed his doctoral studies under the supervision of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr., in 1947, and following a series of brief academic appointments—the longest of which was at Scripps College—joined the history department at Berkeley in 1952.

May was widely regarded as the most distinguished specialist of his generation in the field of American intellectual history. He, more than any other single scholar, was credited with having made intellectual history a basic part of the study of American history instead of an enterprise carried out largely in departments of English, philosophy, political science, and American Studies, as it was through the mid-1950s. As a doctoral mentor, he trained and placed in other major research universities may of the historians of later generations who further developed intellectual history as a speciality within history departments. But central to this influence on the history profession was May’s brilliant book of 1959, The End of American Innocence: A Study of the First Years of Our Own Time, 1912-1917, published by Alfred A. Knopf. This book argued that the cultural rebellions of the 1920s were well underway before World War I and that these rebellions were less dependent upon that war’s impact than earlier scholars had assumed. Covering philosophy, fiction, political thought, literary criticism, historical scholarship, and popular journalism, this book established compellingly that writings in a variety of genres could be interpreted as answering the same questions fundamental to the experience of a generation.

May’s leadership of his field was reinforced and sustained by The Enlightenment in America, a book of 1976 (published by the Oxford University Press) that won the Merle Curti Prize of the Organization of American Historians. This book persuaded scholars that the Protestant culture of late-18th century America rendered the American version of the Enlightenment strikingly different from its European equivalents. Throughout his career he called special attention to the religious aspects of American intellectual history, on which he focused in three other books, Protestant Churches and Industrial America (Harper & Row, 1949), Ideas, Faiths, and Feelings: Essays on American Intellectual and Religious History (Oxford University Press, 1983) and The Divided Heart: Essays on Protestantism and the Enlightenment in America (Oxford University Press, 1991). His last book, published in 1993, was a brief historical study of two pivotal decades of the campus he loved, Three Faces of Berkeley: Competing Ideologies in the Wheeler Era, 1899-1919 (Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies).

But May’s most distinctive work, in the estimation of many of his colleagues and students, was Coming to Terms: A Study in Memory and History (University of California Press, 1987). Unlike the many academic autobiographies that recount professional triumphs and settle scores, May’s autobiography—if indeed that generic term can be applied to this meditation on his own experience-- was limited to the years before he became a famous professor. A probing, self-interrogative reprise of his Berkeley childhood, of left-wing political adventures as a Harvard graduate student in the late 1930s, and of his experiences during the war and in post-war academia, this book conveys more of May’s sensibility and style than anything else he ever wrote. Coming to Terms displays more than any of May’s other books the flashes of wit that so often enlivened his conversations.

May was a dedicated teacher of undergraduates as well as doctoral students. Painstaking in the preparation of his lectures, he continually revised them from year to year to take account of the latest scholarship and of new insights that came to him in the course of his widely-ranging research. His lecture course on American intellectual history developed the theme of Protestant Christianity’s accommodation with Enlightenment, which not only provided undergraduates with a thematically integrated understanding of American history but influenced the many doctoral students who assisted him in teaching the course.

May was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1970, and in 1987 was honored by the Organization of American Historians with its Distinguished Service Award. He served as Pitt Professor of American Institutions at the University of Cambridge in 1971. He received the Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate’s highest honor in 1981 when he was named a Faculty Research Lecturer for that year. May served as chair of his department during the Free Speech Movement of 1964, and was remembered for the honesty and fair-mindedness with which he confronted sharp divisions within his campus community.

May married Jean Louise Terrace in 1941, and after her death in 2002 married Louise Brown, who survived him along with his two daughters and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A unique figure on campus and in the history profession, May was respected as much for his moments of reserve as for his moments of resolution. His students often remember a word of advice he repeatedly offered. “If you ever think you’ve written something really great, think again.” They knew this modest man was also talking to himself. May wrote many great things, but those who knew him personally were deeply affected by the kind of man he was, unassuming yet profound, as in this cautionary quip delivered to his students.

David A. Hollinger 2013

Robert Middlekauff