|

|

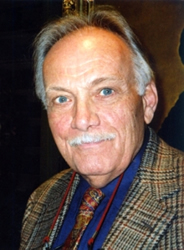

IN MEMORIAM

F. Clark Howell

Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1925 – 2007

Francis Clark Howell, one of the giants of paleoanthropology and the first to bring fields such as geology, ecology, and primatology to bear on understanding human origins, died Saturday, March 10, 2007, at his home in Berkeley after a battle with cancer that was diagnosed the previous year.

Clark, an emeritus professor of anthropology, was one of the founders of modern paleoanthropology.

“His reach was truly global,” said Tim White, professor of integrative biology, who with Howell codirected the campus’s Human Evolution Research Center, founded in 1970 by Howell as the Laboratory for Human Evolutionary Studies.

“Clark’s central importance since the 1950s has been to make paleoanthropology what it is today — that is, the integration of archaeology, geology, biological anthropology, ecology, evolutionary biology, primatology, and ethnography,” said White. “When you look at a modern paleoanthropology project, whether in Tanzania or South Africa or Ethiopia, you find Clark’s stamp everywhere. He personified modern paleoanthropology.”

Howell also left his stamp on the Leakey Foundation, with which he was associated from its establishment in 1968 until late last year. As a founder and trustee of the foundation and a member of the science and grants committee, he steered funding to a broad range of disciplines apart from the “stones and bones” of classical physical anthropology.

“Truly,” said Don Dana, vice president of the foundation’s board of trustees, “he is the father of physical anthropology. He is the one who took paleoanthropology from a fossil-recovery type of science to a science where we had to understand the geology, the flora and fauna, the chemistry, everything. His role, from that point of view, is just enormous.”

Professor White noted that, under Howell, the Leakey Foundation supported Jane Goodall’s work on chimpanzees, Birute Galdikas’s on orangutans, and the late Diane Fossey’s on gorillas, as well as studies of modern human hunter-gatherers.

F. Clark Howell was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1925. Following Navy service during World War II he entered the University of Chicago, from which he obtained his undergraduate Ph.B. in 1949, his A.M. in anthropology in 1951, and his Ph.D. in anthropology in 1953.

He was an instructor in anatomy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis from 1953 until 1955, when he joined the anthropology faculty at the University of Chicago. Howell rose through the ranks to professor in 1962 and subsequently joined the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1970. He retired in 1991, though he remained active until shortly before his death.

Though trained as a physical anthropologist — his Ph.D. dissertation studied the bone structure of the skull base in humans — he was an avid reader of a broad range of scientific literature. If he could not find someone who knew about an area outside his expertise, he would become an expert himself, according to White.

“From the very beginning, he was not one to be bound within subdisciplinary pigeonholes in anthropology,” White said. “He was as much a paleolithic archaeologist interested in prehistory as a physical anthropologist interested in anatomy. He integrated the physical, biological, and behavioral sciences.”

Howell came to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s as the field of African anthropology was becoming more professional and more academic. He worked alongside Louis, Mary, and Richard Leakey, and together they focused attention on eastern Africa as the likely nursery of human evolution, as opposed to other regions of the continent.

He led and participated in digs around the world, ranging from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania to Turkey, Spain, and China. His signature dig was at a site in the Omo basin of southern Ethiopia, where he led a U.S. contingent from 1968 through 1973. It was here that his team’s work revealed fossils and stone tools that helped document a three-million-year succession of human ancestors and collateral species. In this Omo work, Howell established the multidisciplinary standard for modern paleoanthropology.

He also directed, in the early 1980s, the Ambrona Research Project at a human-occupation site in Soria, Spain, dating from the early Acheulian period (0.5-1.2 million years ago). In the late 1980s he codirected a cave excavation at Yarimburgaz in Turkey, and he continued his exploration of sites in Turkey in the early 1990s.

After his retirement, Howell worked with White and colleagues on fossils collected from the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia, where hominids spanning nearly 6 million years of evolution were uncovered by an international team that today includes African scholars trained by Howell.

He mentored numerous students, including young scientists from Ethiopia, Malawi, and Tanzania, often in concert with White and J. Desmond Clark, a Berkeley archaeologist who died in 2002.

According to White, who got interested in the field as a teenager after reading Howell’s 1965 Time/Life Nature Library book Early Man, Howell was an excellent popularizer of the science of human origins. He made the first publicly broadcast film on the subject, an award-winning 1969 MGM TV special called The Man-Hunters. He also was scientific adviser to exhibits on early humans at the California Academy of Sciences, where he served as a trustee from 1976 until 1990 and as president from 1980 to 1982.

Howell was named a member of the National Academy of Sciences as well as a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He also was an honorary fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, as well as of the French Académie des Sciences and the Royal Society of South Africa. He received the Leakey Prize in 1998, the Franklin L. Burr Award of the National Geographic Society in 1993, and in 1998 the Charles Robert Darwin Award for Lifetime Achievement in Physical Anthropology from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. In addition, he was a member of the editorial boards of many journals and a member of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, the East African Wildlife Society, and others.

In recognition of his scientific contributions, Howell’s name was attached by colleagues to seven newly discovered animal species, most of them extinct. The species range from snails to a hyena to an oryx and include one primate: a loris dubbed Galago howelli.

Howell is survived by his wife, Betty Ann Howell, of Berkeley; a son, Brian David Howell, of Berkeley; a daughter, Jennifer Clare Howell, and a granddaughter, Alisa Howell-Smith, of McMinnville, Oregon; and two sisters, Margaret Johnson and Elizabeth Howell of Charlotte, North Carolina.

This memorial resolution is based on an obituary prepared by

Robert Sanders, Office of Public Affairs