|

|

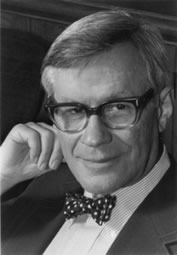

IN MEMORIAM

David Stephen Saxon

President Emeritus

University of California

1920 – 2005

David S. Saxon was a remarkable man of many dimensions. His professional accomplishments, which spanned more than four decades, reflected a powerful intellect and a passionate commitment to science and the life of the mind. His personal qualities – especially his honesty, integrity, and thoughtful perspective on issues large and small – made him an excellent colleague and a wonderful friend.

He came of age during the Depression and the Second World War, and those years left their mark on him as they did on so many others of his generation. His career in higher education coincided with the great postwar flowering of educational opportunity in this country. As a result of these experiences or perhaps simply as a matter of temperament he combined a steadfast realism about the difficulties of life with an optimistic sense of its possibilities.

His extraordinary talents were devoted to the service of two institutions, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California. David earned his B.S. in physics at MIT in 1941, followed by a Ph.D. in 1944. He joined the Los Angeles campus of the University of California as an assistant professor of theoretical nuclear physics in 1947. He later served as dean and executive vice chancellor before being named systemwide provost in 1974; a year later, in 1975, the University’s Board of Regents appointed him president of the UC system, a position that occupied the next eight years of his life. When David stepped down as president in 1983, he came full circle by returning to his alma mater as Chairman of the MIT Corporation, the Institute’s governing board, a post he held with distinction until his retirement in 1990. Both institutions gained immeasurably from his leadership.

David was born in St. Paul, Minnesota on February 8, 1920, the older of two sons. His parents moved to Philadelphia when he was a young boy. His upbringing in a large and lively Eastern European Jewish household instilled in him a deep commitment to both family and education. He wanted to study engineering at MIT, but decided to enroll at a nearby college or university to save on expenses. His father insisted that he apply to MIT and let the family worry about how to pay for it. The entire Saxon clan pitched in to help with the costs of his MIT education; David never forgot how, as he was about to board the train to Boston, his father emptied his pockets to give his son every penny he had.

He met Shirley Goodman, a student at Simmons College, at a dance during his freshman year. Their 1940 wedding was the beginning of a profoundly loving and happy marriage that produced six daughters and an exemplary partnership of more than sixty-five years.

David eventually chose physics over engineering, and his research interests included theoretical physics, quantum mechanics, electromagnetic theory, and scattering theory. From 1943 to 1946, while he was finishing his doctorate, he worked as a research physicist at the MIT Radiation Laboratory, the center of radar development during World War II.

When he was invited to become a member of the physics faculty at UCLA, he sought the advice of an older colleague. His colleague’s view was that UCLA was not a particularly distinguished institution, but it had the advantage of being located in sunny southern California, and if things did not work out he could always play golf. “But everybody says they’re going to build a great university and a great physics department out there,” David replied, and cast his fate with UCLA. Over the next thirty years, as faculty member and administrator, he played a key role in UCLA’s transition from a good to a world-class institution. Although he never did take up golf he was not without avocation. He was a highly skilled musician, both self-taught and teacher educated. He especially excelled at the recorder. A baroque chamber music group met regularly at David and Shirley’s home throughout the 50’s and 60’s.

A few years after his arrival, David found himself embroiled in what became known as the loyalty oath controversy. The University of California Board of Regents, responding to postwar pressures to remove alleged Communists from university faculties, instituted a requirement that all faculty members must sign a loyalty oath as a condition of employment. David was one of thirty-one faculty who refused to sign, along with such distinguished older figures as psychologist Edward Tolman and the medieval historian Ernst H. Kantorowicz. David did not reject the idea of a loyalty oath outright, but he did object to the idea of a university’s imposing a loyalty oath. That, in his view, was orthogonal to everything a university stood for – a free marketplace of ideas in which independent thinking was a valued commodity. David and the other non-signers were reinstated when the courts ruled the firings unconstitutional. Although he did not wish to be remembered for his part in the drama of the loyalty oath, the courage and independence he demonstrated were lifelong characteristics.

As many of his students testified, he was an inspired teacher. At his memorial service in March 2006, one of those students recalled him in the classroom:

His enthusiasm was infectious. When he was developing a proof, he often had a mischievous smile, and when he reached the conclusion, he was visibly delighted by the result, and its physical interpretation. He had an excellent physical intuition which helped us. Sometimes students are immersed in the mathematics and formalism of theoretical physics and lose sight of the underlying physical laws. David kept our focus on fundamental principles and historical perspectives.

Not surprisingly his textbook on “Quantum Mechanics” had a significant influence upon the field.

His style as a theoretical physicist was to focus on “seeing through the problem,” as he put it, and his ability to conceptualize an issue from many angles and in its full complexity was a talent he employed in fields besides the physical sciences. It was one of his great strengths as a university administrator.

I was chancellor of the University’s San Diego campus during David’s presidency – in fact he recruited me – and my fellow chancellors and I met with the president once a month. Newcomers quickly learned there were two things David did not tolerate: foolish remarks and fuzzy thinking. He valued precision and clarity. It was one of life’s ironies that he served as president during a time that he himself described as “an era of pervasive uncertainty.” This tenure spanned the passage in 1978 of California’s Proposition 13 and the early days of the tax revolt, and UC’s budgets were hard hit.

Fortunately, David’s experience at UCLA had taught him what it takes to build and protect a great university. He refused to accept the conventional wisdom – namely, that the 1980s would be a decade of decline for the University. He told the Board of Regents that he endorsed the sentiment (expressed by the famous philosopher, Pogo): “We are surrounded by insurmountable opportunities.” It was a wonderfully direct and optimistic statement.

David was not afraid to speak truth to power. Jerry Brown’s tenure as governor of California coincided with David’s eight years as president of UC, and there was a period in Brown’s governorship when he spent a great deal of time out of state pursuing his ambitions for the U.S. presidency. David once lectured the governor for flitting around the country instead of staying home and tending to the state’s business – including, of course, the University’s business. This incident did not prevent the two of them from having a positive relationship. David once told me the following story. He and Shirley awoke one Sunday morning, looking forward to a quiet day. Then around eight o’clock the phone rang. It was the State police, calling to tell him that the governor was on his way and wanted to drop by for a chat about the University. Before long, Governor Brown appeared, and he stayed for something like six hours. I told David that he showed remarkable forbearance – indeed more forbearance than I could have managed in the same circumstances.

David not only spoke truth to power; he spoke truth to the faculty, which can be much tougher. He liked to quote his predecessor Robert Gordon Sproul’s definition of the faculty: a collection of men and women who think otherwise. David was always attuned to the faculty’s perspective, and he always listened. But ultimately he did what he had to do to preserve the best of the University’s programs, whether or not everyone agreed. Although David was identified with UCLA (because of his long history there) he cared about every UC campus and was scrupulously fair and even-handed. I found him to be realistic about people and pragmatic about problems. But he was always idealistic about the University and its great missions of teaching, research, and public service.

One of David’s most impressive traits as president was his strong intellectual leadership. He took ideas seriously and expected others to do the same. He was particularly troubled by the vast reservoir of scientific illiteracy in American life, and by the failure of higher education to address the problem with the vigor and commitment it deserved. The result of this failure – that even highly educated people must rely on the authority of others where technical issues are concerned – was to him incredible and unacceptable. He was a forceful spokesman on this and on a host of other topics important to our democracy.

Based on long experience, David had a sophisticated knowledge of how research universities work. He knew there was a certain cogency to the concept of the multiversity, espoused by another of his predecessors, Clark Kerr – the idea that the modern university is a collection of loosely connected disciplinary communities, with no single animating principle to hold it together. But it was a perspective that made David uneasy. He always emphasized the underlying unity of the university, the way it transcends social and cultural differences to bring us together in service to the life of the mind. The American research university, he once said, was today’s secular equivalent of the soaring cathedrals of the Middle Ages. Both were imperfect but indispensable institutions. Both inspired a profound faith in the human potential. David’s own faith in the research university gave him the courageous resolve that was the hallmark of his presidency.

Of all the roles he played during his long career, the one he valued most was his role as a member of the faculty. He once spoke about the kind of president he aspired to be: “a university president who is still a member of the faculty and is accepted as such, not as a foreigner but as a native of academe.” More than anyone I have ever known, David Saxon was a native of academe. I would even say that he was a great university president precisely because he was a committed member of the faculty. He represented, quite simply, the best that academic life has to offer.

Richard C. Atkinson