|

|

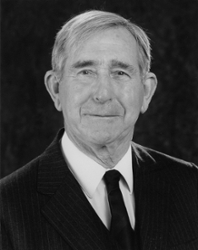

IN MEMORIAM

John Kinloch Anderson

Professor of Classics and Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1924—2015

John Kinloch (“Jock”) Anderson was born on January 3, 1924 in Multan, Punjab (now Pakistan), and died on October 13, 2015 at the age of 91.

From 1937 to January 1942, Anderson was educated at Trinity College, Glenalmond (now Glenalmond College) in Scotland. During the Second World War, he served in the Royal Highland Regiment (the renowned "Black Watch") and took part in campaigns in Europe (Greece, Sicily) and South-East Asia (Burma, behind the Japanese lines), providing vital service in intelligence. After the war, in 1946, Anderson read Classics at Christ Church, Oxford, graduating in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in ancient history. In 1949–50, he attended the British School at Athens and in 1950–52 was a MacMillan Fellow at Yale University. Anderson took part in many archaeological excavations: in the Peloponnese, digging at ancient Corinth, on Chios (Greece), and in Turkey, where he spend several seasons at Old Smyrna (Izmir), and in other expeditions.

Anderson began his teaching career at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, where he was Lecturer in Classics from 1953-1958. During these years his first articles on the archaeology, topography, and art of Achaea, Corinth, and Old Smyrna were published in the Annual of the British School at Athens; and in 1955 his first book, A Handbook to the Greek Vases in the Otago Museum, came out. It was during these years that he met his future wife, Esperance, who was to be a cherished companion to him until her death in 2000. The Andersons moved to Berkeley in 1958 when he was appointed Lecturer in Classical Archaeology in the Classics Department. He spent the rest of his distinguished career at Berkeley, being quickly promoted to Assistant, Associate and then Full Professor, and retiring in 1993.

Anderson published major works on ancient horsemanship, military theory and practice, ancient hunting, and on the 4th C. BCE soldier, moralist-essayist, and historian Xenophon. His book Ancient Greek Horsemanship (1961) is still highly regarded and widely consulted. The book discusses with unique authority the various breeds of horses, harnesses, halters, bits, and saddle cloths, the economics of horse keeping and stable management, as well as everyday practices of equitation, military equipment, and tactics. An appendix publishes Anderson's own translation of Xenophon’s previously rather neglected work, “The Art of Horsemanship”. Equally highly regarded was Anderson's magisterial Military Theory and Practice in the Age of Xenophon (1970), which drew upon a wide range of ancient literary sources and artworks of different kinds. In 1974 followed a smaller and less technical study, pitched to a more general readership and entitled simply Xenophon, in which Anderson succeeded admirably in combining illuminating discussion of literary texts with close historical analysis of that complicated but important period of Greek history, in which Xenophon himself was a major player: Anderson's presentation of all this diverse material is stylish and accessible. In 1985, he published Hunting in the Ancient World, which analyzes deftly (with the help of copious illustrations) a wide spectrum of issues to do with Greek and Roman hunting practices and attitudes from the Bronze Age to Late Antiquity, a period of roughly 2000 years. In addition to these major scholarly monographs, Anderson published many articles on various archaeological, historical, and philological topics. After his retirement, he also wrote in the 1990s, with the illustrator Nancy Conkle, several charming children’s coloring books on different aspects of the ancient world. Anderson was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1966, and was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1976. An eloquent tribute to him was published (in English) by the Russian journal Anabasis in 2014, to honor his 90th birthday.

During his long teaching career in Berkeley's Classics Department, Anderson was a much-loved and versatile contributor to the program at all levels. Although his research was primarily focused on archaeological and historical topics, his knowledge of Greek and Latin literature was extensive and he was just as happy offering courses on Greek literary authors as on Athenian vase-painting, Bronze Age archaeology, or the topography of Classical and Hellenistic Greek sites. His phenomenal memory enabled him to recall and quote extensive passages of almost any author (or so it appeared to us, his less gifted colleagues), from Homer and Aeschylus to Rudyard Kipling and Gilbert & Sullivan, and he generously gave his time to any students who wanted to build their reading skills in informal reading sessions covering all kinds of ancient authors. As a lecturer to undergraduates, he filled large halls with his "Introduction to Classical Archaeology", and many non-Classics majors used to remember their classes with him with warmth and gratitude. The slight but distinctive stammer that accompanied his speech in all contexts proved to be no obstacle to the students' appreciation of his wit, range of knowledge, and evident love of the subject. Likewise as a curator of the Lowie Museum (now the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology), he was always happy to share his expert knowledge of ancient art with students from all over the campus. At the graduate level, he served on numerous MA and PhD committees both in Classics and in the Graduate Group in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology (of which he was one of the founding members); his extraordinary memory, sense of English style, and unfailing supportiveness, coupled with his sheer depth of knowledge, provided a much-treasured resource. Overall, within the Department, his kind, gentle, and humorous manner was much appreciated by colleagues as well as students, and it is no exaggeration to say that he was beloved by all.

He was a well-known and popular figure on the Berkeley campus, remembered by many for the witty minutes in verse that he composed for the Kosmos Club (a faculty dining club to which he belonged), and he was also a founding member and loyal devotee of the Berkeley Greek Club, an informal reading group co-founded by his senior Classics colleague, Louis MacKay.

Up until late in his life, Anderson loved to ride and took a great interest in everything related to horses – past and present, in theory and in practice. He himself won several prizes in the local horse shows, and in his scholarly writings he repeatedly refers to his own experience in handling horses to support his arguments (for example, describing in detail his own experiments with a simple rope halter instead of a bit and a bridle). He was notable too for his keen interest in the whole natural world around him, serving for many years as a docent at the Tilden Botanical Garden, bird-watching avidly, and possessing a wealth of information on the flora and fauna of California. He and his wife Esperance put immense energy into conservation and improvement efforts in the Berkeley Hills and Regional Parks, as well as into the devoted care of their own horses, dogs and, of course, their children, who participated enthusiastically with them in many of these activities.

Professor Anderson is survived by his three children, Elizabeth (and husband Kim Abbott), Katherine Mary (and husband John Schaaf), and John (and wife Karen) and by five grandchildren, a great-granddaughter, and his beloved dog Isla.

Mark Griffith

Andrew Stewart