|

|

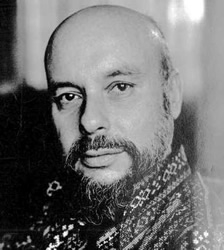

IN MEMORIAM

Simon Karlinsky

Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1924 – 2009

Simon Karlinsky, distinguished scholar of Russian literature and vibrant member of the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures for nearly 50 years, died on July 5, 2009, at the age of 84, at his home in Kensington, California.

Karlinsky was born on September 22, 1924, in Harbin, Manchuria, China, then a largely Russian city, yet anomalously located outside the USSR. His father was a photoengraver; his mother, née Levitina, managed a dressmaking shop. Simon was their only child. He attended Russian schools in Harbin, the last a commercially oriented high school, but early showed both strong literary interests and exceptional musical talent. With the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in the 1930s, conditions for Russians in Harbin became increasingly difficult, especially for Jews, who became victims of attacks and humiliations by Russian fascists. In 1938 the Karlinskys managed to emigrate to the United States, settling in Los Angeles. There, Simon attended Belmont High School and, in 1941- 43, Los Angeles City College.

In January 1944, Simon enlisted in the U.S. Army. After various training camps he was deployed to the European theater, and in 1945 was assigned as a Russian interpreter in occupied Berlin. In 1946, he was honorably discharged from the Army but remained in Berlin as a civilian employee, serving as interpreter, first under the U.S. element in the military government, then (1949) under the State Department in the office of the High Commissioner for Germany. At the time of this transfer Karlinsky received a commendation from his Army superior, noting his "thorough knowledge of American and Russian cultural, scientific, and political thought," and praising his "unfailing good humor, loyalty, and willingness to cooperate." Karlinsky resigned his position in the High Commissioner's office in 1951 and moved to Paris to study composition under Arthur Honegger at the École Normale de Musique. After a year, however, he returned to Berlin to work again as interpreter, this time in the Provost Marshal Branch of the U.S. Berlin Command. In his spare time he continued his musical studies at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik, where he had worked earlier, under Boris Blacher, a then quite important figure who rated Karlinsky “highly gifted in composition” and predicted a good future for him in that field. In May 1956, he received another glowing commendation from his superior, praising "the conscientious and tactful approach [he] had exercised in handling the delicate matter of liaison with the Soviets." He remained in this position until January 1958, when he resigned and returned to the United States.

Eventually, Karlinsky decided that for him the obstacles to a career in music were too great, and he turned to literature. All his life, however, he remained deeply involved with music as a listener, concertgoer and reader. Musicologists, both on and off campus, frequently picked his brain, especially when confronted with difficult texts (like that of Stravinsky’s choral ballet Les Noces) in nonstandard Russian. He translated a wealth of nearly incomprehensible yet indispensable peasant texts for Richard Taruskin’s monograph on Stravinsky, which the author acknowledged with “awed gratitude.” He also published a steady stream of valuable articles and reviews on Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and other Russian musicians for Slavic Review, The Nation, and The Times Literary Supplement. One of these was the butterfly’s wingbeat that set off a thunderstorm in the form of the “Shostakovich wars” that raged for decades following the publication of Solomon Volkov’s notorious Testimony , the composer’s faked memoirs, in 1979. It was Simon’s review of that book, in The Nation, that first gave evidence of Volkov’s chicanery.

In 1958, to resume the main narrative, Karlinsky enrolled as an undergraduate at Berkeley, now concentrating on what had hitherto been more an avocation, Russian literature. He also pursued interests in other literatures, especially French, English, German, and Polish. He graduated in 1960 with highest honors in Slavic languages and literatures. Deciding to do graduate work in the field, Karlinsky moved to Harvard University, obtaining a master's degree there in 1961. His ties to California, however, proved stronger, and he returned to Berkeley for further study, obtaining the doctorate in 1964.

While still a graduate student, Karlinsky served with conspicuous success as a teaching fellow. On his receipt of the doctorate the department appointed him assistant professor, and he then rose very rapidly through the ranks, becoming full professor in 1967. He thus achieved what may well be a record, from undergraduate to full professor in 10 years. In 1967, Simon was chosen to chair the Slavic department, remaining in that post until 1969. He was awarded Guggenheim Fellowships in 1969-70 and 1978. He served the University on numerous committees, making use of his broad learning in many literatures and also music. He taught a wide variety of courses and seminars, including surveys of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Russian literature, Russian modernism, the history of the Russian theater and drama, as well as single-author courses on Pushkin, Gogol, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and others. He sponsored a number of notable dissertations. He retired in 1991.

Karlinsky had a brilliant career as a publishing scholar. His first book (1966), an outgrowth of his doctoral dissertation under Gleb Struve, dealt with the twentieth-century poet Marina Tsvetaeva, a great original master who was then virtually unrecognized and unstudied. Most of her career had been spent in emigration and she was taboo in Soviet Russia, but Karlinsky's pathbreaking book on her set the foundation of what since the collapse of the USSR has become almost a cottage industry. Twenty years later, in 1985, he published a second book on Tsvetaeva, making use of the vast amount of new material that had come to light in the meantime and addressing head-on the issue of her bisexuality. In that same year Karlinsky published another pioneering study that had grown out of his course on the history of the Russian theater and drama. It was a topic almost totally unexplored in any Western language, and the USSR treated it with the usual ideologically charged bias. This book, Russian Drama from Its Beginnings to the Age of Pushkin (1985), not only accomplished the task its title implied but also straightened out a great muddle concerning the early history of Russian opera. Karlinsky considered it his best work.

Earlier, in 1976, Karlinsky had published another epoch-making book, one that marked a major divide in his own life as well as in scholarship on Russian literature: a controversial study of Nikolai Gogol that clearly demonstrated the reflection in Gogol's life and writings of mostly repressed homosexual yearnings. He now began to write a series of articles and reviews on homosexual themes, much of it published in such gay outlets as Christopher Street, The Advocate, and Gay Sunshine, as well as in such mainstream media as the New York Times Book Review, New York Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, and professional journals. Karlinsky was especially active in promoting or defending the reputations of outstanding gay figures in Russian culture, among them the émigré poet Valery Pereleshin, the persecuted Soviet poet Gennady Trifonov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Sergei Diaghilev, and Petr Tchaikovsky. At the same time he worked to combat what he described in Christopher Street as the “self-imposed brainwashing… in the [American ] gay movement” in the 1970s. Subjects that he addressed included the virulently homophobic nature of Marxist-Leninist ideology in practice, to which many Western gay liberationists then subscribed, and which, Karlinsky pointed out, had expressed itself in genocidal terror in the Soviet Union and China.

Other remarkable achievements of Karlinsky were his sparkling commentary on the letters of Anton Chekhov, translated by Michael Henry Heim (1973); his anthology, with Alfred Appel Jr., The Bitter Air of Exile: Russian Writers in the West, 1922-1972 (1977); and his introduction and notes to the correspondence between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson (1979; German expanded edition, 1995). Karlinsky also provided an introduction and notes to a translation of Vladimir Zlobin’s book on Zinaida Gippius. Besides these volumes, Karlinsky published numerous studies in diverse media on a wide variety of topics and cultural figures, from Pushkin and the Russian Romantic writers to Nabokov, the émigré poet Nikolai Morshen, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. He was a brilliant, inspired translator between Russian and English. A Festschrift in his honor, with a full, updated bibliography, For SK: In Celebration of the Life and Career of Simon Karlinsky, was published in 1994.

Karlinsky is survived by Peter Carleton, his beloved companion of 35 years, whom he married in 2008, during the brief period when same-sex marriage was no longer outlawed in California.

Robert P. Hughes 2010

Hugh McLean

Christopher Putney

Richard Taruskin