|

|

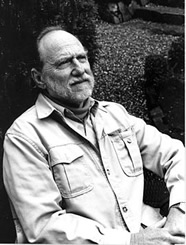

IN MEMORIAM

Leonard Edward Nathan

Professor of Rhetoric, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1924 – 2007

As a teenager in his hometown of El Monte, California, Leonard Nathan fell in love with the poetry of Shelley and Keats and resolved to become a poet himself. And not just any poet but, as he put it once, “an English poet.” By the time he arrived at the University of California, Berkeley on the G.I. Bill in 1947, his ambition had abandoned only its national identity and none of its drive. He would become a “native” poet as voice-centered as the English Romantics but without their soliloquizing lyricism. Nor would he become another of the “California poets,” although his ambition would be nourished over five decades by his life at the University.

Three years in the Army and a year at the University of California, Los Angeles intervened between his graduation from El Monte Union High School and his enrollment at Berkeley, where he majored in English: B.A., 1950, with highest honors; M.A., 1951; Ph.D., 1961 (his thesis was published as The Tragic Drama of W. B. Yeats: Figures in a Dance, Columbia University Press, 1963). He taught for six years at Modesto Junior College before returning to Berkeley in 1960 as lecturer in the Department of Speech. His interest and skills in the performance of poetry made him a vital member of that department, and within a few years this same proficiency made him equally instrumental in the transformation of that department into the Department of Rhetoric. He became the first chair of the newly renamed department in 1968.

Throughout a successful academic career Professor Nathan continued to view his major identity as poet, an identity never dissonant with his teaching and research. He taught, primarily, lower and upper division courses in the oral interpretation of poetry. From time to time he offered upper division and graduate courses in the rhetoric of poetry. The emphasis in all these was a quality which, as the critic Jonathan Holden noted, distinguished his poems from those of his contemporaries: “Nathan’s rhetorical calculation: his consciousness of audience.” A similar distinction marked his gift as teacher. He was deeply admired by both undergraduate and graduate students, upon whom his continuing influence was evidenced by the outpouring of respect and affection from former students upon learning that he had died on June 3, 2007.

Among Professor Nathan’s contributions to the Department of Rhetoric was his course in the rhetoric of translation. The subject reflects one of his major research interests, with the question centering on how one preserves not simply the meaning and harmonies of a poem’s original language but also a sense of its audience and speaker. Professor Nathan’s published work along these lines featured collaborations with the original poet, e.g. the Nobel Prize winner and Berkeley professor of Slavic languages and literatures Czeslaw Milosz, who in turn translated several of Nathan’s poems into Polish, or with a native speaker and writer, e.g. Herlinde Spahr, with whom he collaborated in translating work of the Dutch poet Cees Nooteboom, who, in turn, translated a collection of Nathan’s work into Dutch (De meester van het winterschaap, 1990). A year’s residence in India in the 1960s and friendship with the distinguished Indian poet known as “Agyeya” spurred Nathan’s interest in the rhetoric of translation and led to such publications as a selection of songs by the Bengali poet Ramprasad Sen. For three years Professor Nathan taught part-time in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies and formed a continuing relationship with that department, whose former chair Professor Robert Goldman commented on Professor Nathan’s “insatiable curiosity about language and the ways in which the poetic was expressed in different cultures.” Professor Goldman added that Nathan “had an astonishing sense of the poetic idiom of the great masters of Sanskrit kavya or belles letters. I remember his almost boyish fascination with the dense, impacted structure of the language and his comparison of it to Joyce’s later prose.” This fascination led to The Transport of Love, 1976, his translation of Kãlidasa’s Meghaduta.

The title of his collaborative work with Agyeya, First Person, Second Person (1971), names the communicative paradigm of Professor Nathan’s own poems. He described his career as moving “closer and closer to the human voice in my verse” while at the same time trying “to keep a quality in it—for lack of a better word I call it eloquence—that makes it more than conversation.” This achievement also carried over into his prose, and accounts in part for the popular success of his Diary of a Left-Handed Birdwatcher, 1996, translated into Swedish by Lennart Nilsson, 1998, and already considered in that country as well as the U.S. as a classic in the genre of bird-watching literature.

It is his poetry, however, some 17 volumes, for which he wanted to be remembered, and will be. What were his poems about? Henry Taylor, writing in The Hollins Critic, called Nathan’s general subject the “swift escape of the nearly captured—whether that be vision, phrase, knowledge, or understanding.” The poet himself said that he had two “compulsive themes”: “how to make things fit together that don’t but should” and “getting down far enough below a surface to see if something is still worth praising.”

Memory is of course crucial to the creative process—traditionally memory was mother of the muses as well as the fifth art of rhetoric—and it is a sad irony that it was this faculty which late in life began to fail him. As long as he could, he continued his final collaboration, with Professor George Hochfield, on translating the poetry of the Italian poet Saba. And he continued creating his own poems, a few in the early stages of his affliction exploring or attempting to come to terms with his own failing powers:

He has come so far, so near, but sleep

bewilders him and he forgets why

he is here and where he is.

He stands in the middle of some final room

as in a dark wood, waiting for memory

to catch up. It won’t.

Dawn arrives instead, a granddaughter

who leads him by the merest love

back to the wrong world.

Among his many honors, Professor Nathan received two Humanities Research Fellowships from the University, the National Institute of Arts and Letters prize for poetry, an American Institute of Indian Studies Fellowship, a translation award from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Phelan Award for Narrative Poetry, and three silver medals from the Commonwealth Club of California. Upon learning of his death, former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser wrote, in part, “I will go to my grave not knowing half of what he knew about literature, about writing, and about life. . . . He was among the best and most intelligent writers of our age, and, more importantly, among the finest souls that we have been blessed to live our lives among.”

He is survived by his wife Carol of San Rafael, a son, Andrew, of San Anselmo; daughters Julia of Harlingen, Texas, and Miriam of Vancouver, Washington; and four grandchildren.

Thomas O. Sloane

Seymour Chatman

George Hochfield