|

|

IN MEMORIAM

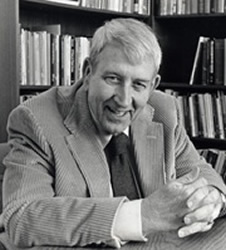

James R. Gray

Senior Lecturer in Education, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1927 – 2005

James R. Gray, founder of the National Writing Project, an influential and highly regarded educational reform network, died October 31, 2005, at age 78.

Born in Madison, Wisconsin on June 13, 1927, Gray grew up in Whitefish Bay, a suburb of Milwaukee. He returned to Madison to attend the University of Wisconsin, where he majored in comparative literature. To pay for college, he earned money by playing in a dance band and working summers in the Milwaukee breweries. After obtaining a master’s degree, he took on some menial jobs. “I didn’t qualify for anything,” he wrote in his autobiographical work Teachers at the Center, “though all the personnel directors said I was overqualified.” He returned to the university to earn a teaching credential and embarked on a career that led, in the 1950s, to a position teaching English at San Leandro High School in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Gray approached teaching with the passion characteristic of his approach to life. From apple boxes, he built six-foot-high bookshelves along the walls of his high school classroom, then filled them with books he had found scouring Berkeley used book stores. “I expected students in all my classes to plunge into this library. I believed that the best thing I could do for high school students was to cultivate their love of books.”

In 1961, Gray became a member of the Department of Education at the University of California, Berkeley, supervising students preparing to teach English, a position that allowed him to develop that faith in the talent of others that was a major source of his leadership. He also taught courses in the English and rhetoric departments at the University, believing it was important to forge links between education and academic disciplines.

In 1963, Gray was appointed the director of language arts for the Department of Defense Dependent Schools in Europe, where he directed a revision of the whole language arts curriculum. After he returned to UC Berkeley, he became one of the architects of the short-lived but highly regarded California English Specialist Program. He also served as summer director of the University of Hawaii National Defense Education Act Institute.

In 1974, after spending years as a classroom teacher and as an educator of teachers, Gray acted on a notion he had long pondered: successful classroom teachers, he believed, are the best teachers of other teachers. During that summer, when the national media were reporting that American students could not write, Gray brought together 25 highly talented teachers for an institute at UC Berkeley, to share with each other what they knew about the teaching of writing and to prepare them for conducting workshops for other teachers. Gray coupled his respect for teacher expertise with another common sense notion: teachers of writing should write. So the institute participants spent a good part of each day practicing the craft they were responsible for imparting to their students. This combination of activities became the model for the summer institute that has continued on the Berkeley campus, uninterrupted to the present day, each year bringing a new group of outstanding classroom teachers to the university.

The project grew to become a powerful teacher resource because Gray organized the summer fellows into teams that would take what they knew back into the schools. Rather than lecture to their fellow teachers, writing project fellows put their colleagues to work trying out the concepts they were advocating, taking what they had learned back to their own classrooms for trial, and then reporting on what was and what was not effective. Classroom teachers, Gray believed, are the best critics of their own work.

Gray put these then radical ideas together to create the Bay Area Writing Project, the model for the professional development network for teachers that has, as the National Writing Project, expanded now to include nearly 200 university-based locations in 50 states, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Gray served as executive director of the project until his retirement in 1994 and thereafter remained on the organization’s board of directors.

The National Writing Project, now funded in part by the U.S. Department of Education, has worked with over two million teachers across the country and has become an increasingly visible advocate for the importance of the teaching of writing. Over the years it has taken on new challenges, among them working with teachers of English language learners, sponsoring programs for new teachers, and providing teachers with the skills to bring new technology to their writing classrooms. And Gray’s “teachers teaching teachers” model has remained at the heart of all these initiatives.

For many years Gray was a leading force in organizing the yearly Central California Council of Teachers of English conference at Asilomar. In 2003, Gray received the Distinguished Partners in Learning Award from the National Council of Teachers of English. He was the 2004 recipient of the California Association of Teachers of English Career Achievement Award and was recognized by both the California Legislature and the United States Congress for his outstanding contributions to education.

Beyond his professional life, Gray was a warm and vital man who loved classical music, model trains, Dickens, gardening, and a 5 p.m. martini. He was an avid collector of books and stamps and something of an expert on the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. No denizen of Berkeley’s gourmet ghetto, he enjoyed shepherding visitors toward the more substantial fare offered at Brennan’s Hofbrau at Fourth Street and University Avenue, where the food was as honest and free of frills as the man himself. Above all he valued fellowship, forging lasting friendships with colleagues and students, with persons met by chance while traveling or attending a concert, with bookstore owners, music store clerks, and a great assortment of other persons he felt privileged to get to know.

He is survived by Stephanie, his wife of 48 years, and his daughter, Laura Zagaroli, both of Danville, California.

Richard Sterling

Art Peterson

Mary Ann Smith