|

|

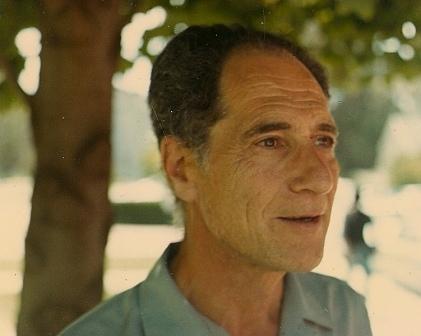

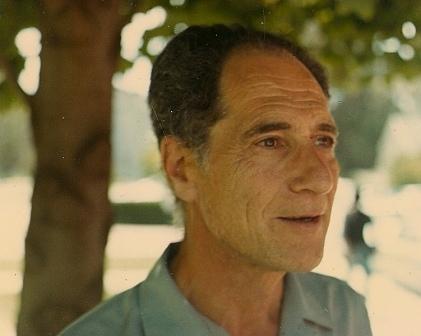

IN MEMORIAM

Gerhard Hochschild

Professor of Mathematics, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1915 - 2010

Gerhard Hochschild, professor emeritus of mathematics, died peacefully at home after a long and satisfying life on July 8, 2010, at the age of 95. His daughter Ann was at his bedside. He is survived by his daughter Ann, his son Peter, and two grandchildren. His beloved wife Ruth predeceased him in 2005.

Gerhard Hochschild was born on April 29, 1915, in Berlin, Germany, where his father was a patent attorney who also had a degree in engineering. Soon after Hitler came to power in 1933, Gerhard’s father sent Gerhard and his older brother to the Union of South Africa for their safety. There Gerhard continued his education, enrolling in the University of Capetown. He supported himself by working as a photographer’s assistant and by funds from the Hochschild Family Foundation, which had been established by a cousin of his grandfather to aid members of the extended family in times of need. Gerhard received a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Capetown in 1936, and a Master of Science degree in mathematics in 1937. Stanley Skewes, a mathematician on the faculty at Capetown, who had mentored Gerhard, arranged an appointment for him as a junior lecturer so that he could continue his studies for another year at Capetown.

In 1938, with the support of Skewes, Gerhard applied and was admitted to the mathematics Ph.D. program at Princeton University, where he completed his doctoral degree in 1941. He became a naturalized citizen in 1942. After serving in the U.S. armed forces during the war, and after postdoctoral positions at Princeton University and Harvard University, he settled into a tenure track faculty position at the University of Illinois in 1948. Rising quickly through the ranks, he was promoted to a full professorship in 1952, and his work from these years won him wide acclaim. He was the first to introduce and study the cohomology groups of associative algebras and their modules, and he went on to show how to use cohomological tools in the study of both local and global class field theory. With Jean-Pierre Serre he showed how to define a spectral sequence for the cohomology of a group extension. Today, these are fundamental tools in universal use in mathematics.

Gerhard Hochschild’s connection with Berkeley began in 1955, when he accepted a position as visiting professor of mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley, for the academic year 1955-56. When he arrived, he found a mathematics department that was very different from the Berkeley mathematics department of today or indeed from what it had become in the early 1960s. It was a small department with a total of 19 faculty in all professorial ranks. The department had some very real strengths, including a distinguished group of statisticians and probabilists, but this group had split off in 1955 into a newly formed separate department of statistics. There were also strengths in a number of other areas—analysis, including partial differential equations (PDEs) and functional analysis, computational number theory, and logic. But algebra, and geometry and topology, fields that were rapidly developing at the time, were seriously underrepresented among the faculty in 1955. The department was poised to grow substantially in the next few years and the hope was through this growth to remedy these programmatic weaknesses. Inviting Hochschild, a prominent senior algebraist of considerable stature, to visit for the 1955-56 year was a first step toward this program. Hochschild did enjoy his year’s visit.

From past experience, however, the mathematics department knew that it would encounter difficulty in permanently attracting senior faculty to Berkeley in these areas of weakness because of concern about isolation. Further, it would be difficult to attract outstanding junior faculty in these areas absent senior faculty. Nevertheless the department succeeded in hiring three outstanding assistant professors in these areas in 1956—Emery Thomas, Bertram Kostant, and James Eells. The department under John Kelley’s leadership decided on a strategy of hiring clusters of senior faculty in the underrepresented areas. In the fall of 1957, the department approached Hochschild and Maxwell Rosenlicht and offered them both full professorships at Berkeley to begin in 1958. Each was informed of the offer to the other and the strategy proved to be a success when both accepted, thus providing a core of senior algebraists at Berkeley.

The following year, this cluster strategy was applied in geometry and topology, with offers made to Edwin Spanier and Shiing-Shen Chern. Both accepted, with Spanier arriving in 1959 and Chern deferring arrival for a year because of prior plans. Knowing that Hochschild and Rosenlicht had already moved to Berkeley perhaps increased the likelihood that Chern and Spanier would accept these offers. Also in 1960, Stephen Smale, Morris Hirsch, and Glen Bredon accepted appointments as assistant professors. By 1960, the number of faculty in professorial ranks had grown to 44, with a much improved balance of fields, and a vigorous and vibrant intellectual atmosphere. Hochschild’s appointment and his decision to come to Berkeley was one of several key factors in this change.

Beginning a bit before he first visited Berkeley, Gerhard’s research interests began to shift from the homology of associative algebras and applications of homological algebra to class field theory, to the study of Lie algebras and Lie groups. Gerhard focused especially on their linear representations, their cohomology, and Lie group and Lie algebra extensions. In Berkeley, Gerhard found in Bert Kostant someone with similar interests in Lie algebras and Lie groups; and this common interest led to a collaboration, with two published papers on differential forms and cohomology of Lie algebras. Two coauthors of this memorial (Moore and Wolf), both with interests in Lie groups and Lie algebras, arrived in Berkeley in the early 1960s and found many common interests with Gerhard, which in turn led to many fruitful scientific discussions.

Over the next 25 years, Gerhard produced a steady stream of important and fascinating papers on Lie algebras, Lie groups, their representations, and cohomology. Many of these were in collaboration with Dan Mostow of Yale University, which represented a career-long scientific collaboration and friendship. He also became interested in Hopf algebras and wrote several papers on them and their connections with Lie groups. Gerhard supervised the doctoral dissertations of 22 students at UC Berkeley, and overall in his career he had 26 doctoral students with 122 descendants, according to the Mathematics Genealogy Project. His achievements were recognized by election to the National Academy of Sciences and to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1980, the American Mathematical Society awarded Gerhard its Steele Prize for work of fundamental or lasting importance, citing in particular five papers published from 1945 to 1952 on homological algebra and its applications. Gerhard replied that while he was deeply honored by the society’s consideration of his work for a prize, he was, for personal reasons, unable to accept the Steele award. A friend has commented that the reason was simply that Gerhard did not believe in prizes.

As a distinguished and senior algebraist in the department, he was called on frequently for advice and counsel on departmental matters. His opinions and advice were wise and incisive and offered with his characteristic ironic wit. He also served as advisor and mentor for many junior faculty members in algebra, and his guidance was deeply appreciated by the many colleagues who sought it. He had, however, a lifelong aversion to and dislike of what he termed academic bureaucracy. One result of this was that he consciously, consistently, and with self-deprecating good humor, avoided all attempts to convince him to assume any administrative positions such as chair or vice chair in the department.

Gerhard was a longtime smoker who, when he did give up smoking, continued for some time to carry an unlit cigarette between his fingers and sometimes between his lips, perhaps as a memento of his former smoking days. He changed the cigarette occasionally when it became too decrepit. But he never lit it!

Until July 1, 1982, University policy required retirement of tenured faculty on July 1 following their 67th birthday. Effective July 1, 1982, this policy had been changed to require retirement on July 1 following the 70th birthday. As Gerhard was born on April 29, 1915, he was by two months in the last cohort that was subject to the earlier mandatory retirement age. Gerhard saw this policy as academic bureaucracy at its worst. The result was that he retired on July 1, 1982, and entered the University’s phased retirement program for three years, teaching part-time until retiring fully on July 1, 1985.

Some years prior to his retirement, Gerhard became interested again in photography and took it up as a hobby with a deep and abiding commitment. He was entirely self-taught and relied on reading books on photography. However, his interest in photography dated back to his boyhood years in Berlin, and to his work as a photographer’s assistant while a student in Capetown, South Africa. His primary interest was in landscape photography, especially of desert scenes in the U.S. Southwest. He would periodically go off on expeditions by himself, with his camera gear, which included a Hasselblad 4x4 and later a view camera, driving thousands of miles looking for just the right scene and just the right lighting, sometimes staying away for a month. His favorite site was southeastern Utah, although Alaska was also a destination of his expeditions; and he also photographed San Francisco Bay. Ansel Adams was his model and his hero, and Gerhard’s work does remind one of some of the work of that famous photographer. Gerhard was encouraged by friends to have a show featuring his work, but he declined all such efforts. His photography occupied him for decades, but toward the end of his life, his health did not permit him to go off on long expeditions.

Calvin C. Moore

Kenneth A. Ribet

Joseph A. Wolf

2011