|

|

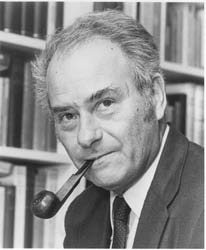

IN MEMORIAM

Eugen Weber

Professor of History, Emeritus

Former Dean of the College of Letters and Science

UC Los Angeles

1925 – 2007

When Eugen Weber died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 82, UCLA lost a distinguished administrator, a brilliant teacher, and perhaps the most renowned American scholar of modern France. It was a loss keenly felt in the world of letters both in Europe and the United States, with immediate obituaries in the The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Star (Toronto), The International Herald Tribune, The Guardian, Le Figaro, and Le Monde.

A member of the UCLA faculty since 1956, he helped, in the words of his New York Times obituary, “to build the History department into one of the nation’s best.” He served as Chair of History, Dean of Social Sciences, and Dean of the College of Letters and Science from 1977 to 1982. He was the rare faculty member who both was Faculty Research Lecturer (1986) and received the Distinguished Teaching Award (1992). He was the first incumbent of the university’s endowed chair in Modern European History, which is now named in his honor. Even after his formal retirement in 1993, Eugen returned to teach lower-division courses in Western Civilization.

His accessible style made him popular among students, historians and the public in the United States as well as in France, where his books on modern French history are considered classics. Over the years, hundreds of thousands of students got their first taste of modern European history from Eugen’s best-selling textbooks, A Modern History of Europe (1971) and Europe Since 1715: A Modern History (1972).

Eugen was also a familiar, charming presence to Americans who saw his acclaimed 52-part lecture series, “The Western Tradition,” produced by the Annenberg Foundation for PBS in 1989. There he brought his typical joie-de-vivre to five thousand years of history from Egypt and Mesopotamia to the 20th century. The episodes still appear with some regularity on cable television. Eugen would be amused that he has attained immortality in cyberspace as well as in his chosen venue, the library.

Eugen Weber was deeply European in cultural and intellectual formation and deeply American in his outlook. He was born in Bucharest, Romania, the son of Sonia and Emmanuel Weber, an industrialist. At age 12, he was sent to boarding school in Herne Bay, in southeastern England, and later to Ashville College in the Lake District.

After graduating in 1943, Eugen joined the British Army and was stationed in Belgium, India and occupied Germany. He rose to captain in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, one of Britain’s oldest regiments. After his service ended in 1947, he attended Cambridge University. While at Cambridge, Eugen spent a yearlong-interlude in Paris, studying at the Institut d’Études Politiques and teaching English at the suburban Lycée Lakanal. He fell for France, he said, “just as one falls into love.” He received his degrees from Cambridge: B.A. (1950), M.A. (1953), and M. Litt. (1955).

His first book, The Nationalist Revival in France: 1905-1914 (1959), traced French right-wing nationalism from the Dreyfus affair to the outbreak of World War I. In this book as well as in his Action Française: Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France (1962), Eugen examined how French nationalism had changed from a humanitarian, Enlightenment-based movement in the early 19th century into an angry, “tribal” and “exclusivist” movement in the 20th century. Despite its affinities with the historic right, the virulent, xenophobic and radical nationalism of the 20th century, he argued, was statist and anti-individualistic. He wrote extensively on fascism, and was particularly interested in how the extremes of right and left sometimes converged.

Perhaps his most influential book was Peasants Into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914 (1976) which demonstrated how a country that was still largely rural, “inhabited by savages” and a hodgepodge of cultures was transformed in the half-century after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Weber maintained that before the 20th century, France was largely “a Parisian political project rather than a national reality.” Modern French identity, he said, was a relatively recent creation, a product of mass education, conscription and the coming of modern communications. In this book, as in his others, Eugen shows his gift in using compelling anecdotes from everyday life to make his writing so enjoyable. This book received prizes in both France and the United States and has now become the standard view. An international conference at UCLA celebrated the 30th anniversary of its publication in 2006.

Though Eugen’s ideas and interests ranged across all aspects of European history, his true loves were the culture and politics of France. Among his other scholarly books are Paths to the Present: Aspects of European Thought From Romanticism to Existentialism (1960); Varieties of Fascism: Doctrines of Revolution in the Twentieth Century (1964); The European Right: A Historical Profile (1965), which he edited and wrote with his UCLA colleague Hans Rogger; France: Fin de Siècle (1986); The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s (1994); and Apocalypses: Prophecies, Cults and Millennial Beliefs Through the Ages (1999). A recent indication of the esteem in which Eugen was held in Britain was his invited introduction to the deluxe edition of Braudel's The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II by The Folio Society (London, 2000).

Eugen’s work was admired in France, where he was interviewed in newspapers and on television as a cultural “personality.” Tony Judt of New York University observed in a New York Times review: “On the whole, the French write their own history and write it with much sophistication. But occasionally they come across a foreigner who does it differently or better, and then, with much fanfare and generosity, they adopt him for their own. Such is the case of Eugen Weber.”

Eugen’s books and articles have been translated into more than half a dozen languages, and he earned many accolades for his scholarship, including membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society. He held fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies and the Fulbright Program, as well being decorated with the Ordre National des Palmes Académiques.

In his introduction to a book of collected essays, My France: Politics, Culture, Myth (1991), Eugen admitted to having a mind that was “more like a jumbly hayloft than an orderly library.” Tireless in pursuit of detail, he delighted in sharing the fruits of a lifetime spent in provincial archives. But his curiosity knew few bounds; he was for many years the reviewer of mystery novels for the Los Angeles Times.

The French have always put a great emphasis on style, and so did Eugen Weber. It could be found in his elegant writing, his scintillating conversation, and his generous hospitality to students, colleagues, and visiting scholars. His sense of humor was omnipresent – sometimes biting but never cruel. He knew very well that he represented in many ways an older time. As he wrote, "Few 20th-century historians of 19th-century Europe had the good fortune to be born in the 19th century: that was where Romania still lived between the wars." His UCLA colleagues and students were immensely fortunate to have his presence (and that of 19th century Europe) among them for more than a half-century.

It was in London that he met Jacqueline Brument, an art history student visiting from Paris. They married in 1950 and Eugen always said that he wrote his books for her. What she did not find clear, he revised. Their 57-year marriage was filled with books, travel, art, good food and good wine, and many devoted friends. Jacqueline is his only immediate survivor.

Ronald Mellor

Lynn Hunt

Bariša Krekic

Robert Wohl