|

|

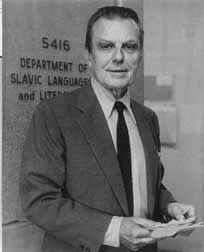

IN MEMORIAM

Czesław Miłosz

Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Emeritus

Berkeley

1911–2004

Czesław Miłosz (d. 14 August 2004), Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the University of California, Berkeley’s only Nobel Prize winner from the Division of Arts and Humanities, was witness to much that was central to the history of the twentieth century. He was born on 30 June 1911 in Szetejnie/Šateiniai, a small town in rural Lithuania, then a part of the Russian Empire. His parents, Aleksander and Weronika (née Kunat), were members of the long polonized lesser Lithuanian nobility. Miłosz would always place emphasis upon his identity as one of the last citizens of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a place of competing and overlapping identities. This stance—not Polish enough for some, certainly not Lithuanian to others—would give rise to controversies about him that have not ceased with his death in either country.

Aleksander Miłosz, an engineer, was drafted into the tsarist army during World War I, and Miłosz claimed memories of the Russian Revolution. The family decided to settle in then Polish Wilno in 1921, where Czesław Miłosz finished gymnasium in 1929 and began studies of Polish literature and finally law at the Stefan Batory University. In April 1931 he cofounded the Polish avant-garde literary group “Żagary” (a polonized Lithuanian word meaning “Brushwood”). At this time he made his first trip to Paris, where he met a distant cousin, Oskar Miłosz, a French-language poet and Lithuanian patriot, who stimulated his lifelong interest in Swedenborg and his skepticism of traditional models of Polish nationalism. In 1933 Miłosz published his first volume of poetry, and in 1934 he received the degree of master of law from the Stefan Batory University and set out on a yearlong fellowship in Paris. In 1936 Miłosz was made a commentator on literature for Radio Wilno, but he was dismissed after a year for his “leftist” views. After travels in Italy, Miłosz began to work for Radio Warsaw.

At the outbreak of World War II, Miłosz first sought refuge in Romania but then returned to Wilno, seeking a Lithuanian passport. After the seizure of the city by the Soviets in June 1940, he made his way clandestinely to German-occupied Warsaw, where he joined his future wife Janina Dłuska and became a central figure in the literary underground using the pseudonym Jan Syruć. At this point he joined a socialist underground group called “Wolność” (“Liberty”), and in 1941 he took an official job as a janitor at Warsaw University Library. During secret evening literary gatherings he became close friends with the writer Jerzy Andrzejewski, the literary critic Kazimierz Wyka, and the philosopher Tadeusz Kroński.

In January 1944 he married Janina Dłuska. After the Warsaw Uprising of August–October 1944, the couple took refuge in Cracow, in the house of Jerzy Turowicz, who would himself go on to become one of the towering figures of postwar Poland. Turowicz became the editor of the Catholic intellectual newspaper Tygodnik Powszeczny (Universal/Catholic Weekly), the most independent public voice in Communist Poland. From his “exile” in Cracow, Miłosz would take an active role in the reemerging literary life of the Polish People’s Republic.

From December 1945 Miłosz was in the Polish diplomatic service in New York, and from 1947 he was the cultural attaché in Washington. During this time he continued to publish poetry and translations in Poland. A short visit to Poland in June 1950 made clear the advancing sovietization of the country. In the fall of that year he became the first secretary in the Polish embassy in Paris. During a visit to Poland in December state authorities withheld his passport, only to return it after the intervention with Premier Boleslaw Bierut of a high-ranking Communist official, Zygmunt Modzelewski.

On 1 February 1951 Miłosz requested political asylum in France. In the May issue of the émigré journal Kultura—edited by another giant of postwar Polish culture with whom Miłosz had lifelong contacts, yet another “Lithuanian,” Jerzy Giedroyc—the poet gave one explanation for his actions: “the imitation of Soviet models had become obligatory for writers in Poland.” In 1953 Giedroyc’s Literary Institute published Miłosz’s The Captive Mind, still considered one of the most probing analyses of the allures of power for intellectuals ever written.

Miłosz continued publishing poetry and essays in Kultura while becoming persona non grata in Poland, and mostly ignored, with the exception of occasional attacks by mouthpieces of the regime like Jerzy Putrament, who was the basis for the character study for “Gamma, the Slave of History” in The Captive Mind.

In 1960 Miłosz moved to Berkeley at the invitation of Professor Francis J. Whitfield and the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. He quickly advanced to professor. He settled here with his wife and two sons on Grizzly Peak Boulevard, where he wrote, among other things, his Visions from the San Francisco Bay. In 1974 he received an award from the PEN Club for his translations of Polish poetry into English. A Guggenheim Fellowship followed in 1976 and an honorary doctorate from the University of Michigan in 1977. In 1978 he retired from the University, receiving the Berkeley Citation and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature for the entirety of his work.

At Berkeley, Miłosz had a devoted audience for his courses on Dostoevsky and on Polish literature. He had continued to write poetry and essays in Polish during his years in Berkeley, seeing himself very much as a poet deprived of a natural readership, writing in a little understood language, publishing mostly in the leading emigré journal in Paris for a small readership of Poles abroad, and for a growing audience of Poles in the People’s Republic who could find access to his works in clandestine editions. During these years he developed important ties with American poets, including Robert Hass, who became the translator of the bulk of his poetic work into English.

On 9 October 1980 he received the Nobel Prize for the entirety of his work, and in the spring of 1981, during the briefly legalized existence of Solidarity, he visited the People’s Republic of Poland. This was his first return to Poland since 1950, and for the first time since his defection 30 years earlier, volumes of his poetry were published in Poland. Part of one of his poems was engraved on a monument to workers slain in disturbances following the 1970 strikes on the Pomeranian coast that was erected by Solidarity in Gdansk in December 1980. With martial law in Poland in December 1981, Miłosz again became a nonperson.

The 1980s were a period of great international recognition for Professor Miłosz’s work in the West. In 1982 he gave the Norton Lectures at Harvard University and became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York. In 1989 he received the National Medal of the Arts of the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts. His wife Janina died in 1986.

With the changes in Eastern Europe beginning in 1989, Miłosz became a regular presence in his homelands of Poland and Lithuania. He was made an honorary citizen of Lithuania in 1992 and of the city of Cracow in 1993, where he began spending the summer months with his second wife, Carol Thigpen, historian and former dean at Emory University. Miłosz was likely one of the few, but notable, Nobel Prize winners (Thomas Mann comes to mind) who wrote more, and perhaps more important things, after the award than before. He and Carol eventually came to spend the entire year in their newly chosen home of Cracow. Carol Thigpen died in August 2002. Czesław Miłosz continued to write, both poetry and prose, almost until the end of his life. He died in Cracow at age 93 on 14 August 2004. His funeral was a state event in the ancient cathedral church of St. Mary, presided over by the cardinal archbishop of Cracow and attended by important figures from Polish cultural and political life, in addition to representatives from Berkeley. His body was accompanied by thousands through the streets of his adopted city to its resting place in the Polish equivalent of Poets’ Corner in the “Church on the Rock.”

David Frick

John Connelly

Robert Hass