|

|

IN MEMORIAM

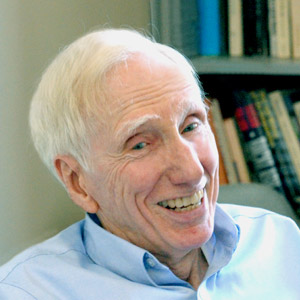

Robert Neelly Bellah

Elliott Professor of Sociology, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1927 - 2013

Robert Neelly Bellah died on July 30, 2013, following heart valve surgery. Up to the moment of his death, at age 86, he remained intensely intellectually vibrant, politically and morally engaged, and undiminished in his scholarly powers. He had published his magnum opus, Religion in Human Evolution, in 2011 and was at work on a book about the crisis of modernity.

Bellah was the preeminent sociologist of religion of his generation, but did not fit easily into conventional academic or professional categories. Through his writings and public lectures, he addressed religious thinkers and theologians, political leaders and philosophers, and the morally engaged public, as well as sociologists, historians, and students of religion more broadly. In 2011 he gave lectures at Peking University, including the keynote address at the Beijing Forum, and in May 2013, he gave the Paul Tillich Lecture at Harvard.

Bellah’s intellectual contributions, like his broad erudition, reflected a continuing “search for meaning and wholeness” (p. xviii, Beyond Belief, 1970) in what he saw as a fractured, inevitably flawed world. A son of the American West – born in 1927 in Altus, Oklahoma and then raised in Los Angeles after the death of his father – Bellah was deeply shaped by his time at Harvard, from which he graduated summa cum laude in 1950 and from which he received his PhD in 1955. He wrote that he saw Harvard at its best and at its worst, the latter referring to Harvard’s threat, during the McCarthy era, to withdraw his graduate fellowship and to deny him a promised teaching appointment unless he exposed his associates from his undergraduate period as a member of the Communist Party. Rather than accept these terms, Bellah went to Canada from 1955 to 1957, where he held a post-doctoral fellowship at the Islamic Institute at McGill University. In 1957 he accepted a teaching position at Harvard, this time without conditions. In 1967, Bellah moved to Berkeley where he remained for the rest of his career.

Bellah was drawn to the study of cultures far outside contemporary America, and yet he is probably best known for his work on America. His undergraduate thesis was a study of Apache kinship, and his first book, Tokugawa Religion: The Values of Pre-Industrial Japan (in print continuously since its publication in 1957), analyzes how Japanese Neo-Confucian thought contributed to a distinctively Japanese path to modernity. In the late 1950s, Bellah, along with the anthropologist Clifford Geertz – both were students at Harvard of the leading sociological theorist of the era, Talcott Parsons – revitalized the study of religion by focusing on the role of religious symbolization. Bellah’s 1964 paper, “Religious Evolution,” was a tour de force, analyzing parallel “breakthroughs” in the first-millennium BCE of Confucian thought, Buddhism, ancient Judaism, and Greek philosophy. In each of these cases, religious symbols became more “differentiated” from the natural and human world, as more autonomous religious organizations of priests or philosophers posited a transcendent realm in terms of which earthly realities could be judged. “Whether the confrontation was between Israelite prophet and king, Islamic ulama and sultan, Christian pope and emperor or even between Confucian scholar-official and his ruler,” Bellah wrote, “it implied that political acts could be judged in terms of standards that the political authorities could not finally control.”

Bellah himself engaged in this sort of moral critique, most notably in The Broken Covenant (1975), where he criticized America’s pursuit of wealth and power and its racist efforts to dominate other peoples, in contradiction to its own civil religion. His idea that moral criticism was possible only in light of shared traditions inspired his influential essay, “Civil Religion in America” (1966), as well as his co-authored books, Habits of the Heart (1985) and The Good Society (1991). In this period, Bellah delved ever more deeply into American history and culture, seeking both to probe the cultural roots of its failures and to inspire Americans to live up to its historic ideals. In Habits of the Heart, he and his collaborators (Richard Madsen, William Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven Tipton) drew on interviews with middle-class Americans to describe the ways individualism and market ideology undermined effective political institutions and the very sense of mutual commitment that Americans themselves sought.

In Religion in Human Evolution, Bellah returned to the large historical and comparative themes of his earlier work on religion, but embedded that history in a grand cosmology, starting with the origins of the universe, and moving through all of biological evolution, as it contributed to the capacities that made religious experience possible –particularly play, pair bonding, and the nurture of helpless infants. Constructing this grand narrative required mastering vast literatures in evolutionary biology, paleontology, archaeology, and other disciplines. But this narrative was crucial not only to telling the story of religion in human societies, but more centrally in establishing the common roots from which the great world religions, in all their distinctiveness, emerged. The book makes clear that every tradition depends on rich myths and ritual practices that make its symbols live. Even recently-developed capacities, like that for “theoretic” thought, which might enable humankind to save itself from current dangers, depend on deep connection to both the specific and the universal in our collective history. Thus, in probing the religious traditions of India and China, as well as those of the Greeks and the ancient Israelites, Bellah was writing a universal history that could ground a shared commitment to confront a common global future. He ends Religion in Human Evolution not only arguing for mutual respect among diverse religious truths, but warning that “theory that has come loose from its cultural context can assume a superiority that can lead to crushing mistakes.” He continues, “If we could see that we are all in this, with our theories, yes, but with our practices and stories, together,” we might come closer to “Kant’s dream of a world civil society that could at last restrain the violence of state-organized societies toward each other and the environment.”

Bob Bellah was a towering intellectual figure and a remarkable friend, colleague, and teacher. Tributes after his death evoked not only his brilliance, but his surprising compassion and kindness toward terrified undergraduates, demoralized graduate students, and others to whom he reached out with understanding over his career. He is remembered as generous, loyal, high-minded, and yet also irreverent, funny, and down-to-earth. His work attempted to hold together what he believed modern thought conspires to drive apart–reason and moral understanding. For him, reason was the search for the good, and reason devoid of moral purpose was utterly irrational.

Bellah was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1967. In 2007, he received the American Academy of Religion Martin E. Marty Award for the Public Understanding of Religion. Bellah received the National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton in 2000.

Bellah was predeceased by his wife, the former Melanie Hyman, to whom he was married for sixty-one years, and by his daughters Tammy and Abby. He is survived by daughters Jennifer Bellah Maguire and Hally Bellah-Guther, and by his sister, Hallie Reynolds, and five grandchildren.

Ann Swidler

Claude Fischer