|

|

IN MEMORIAM

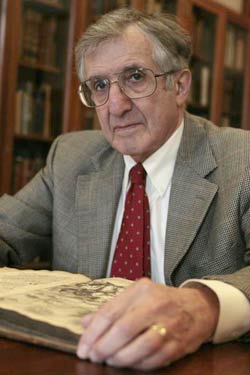

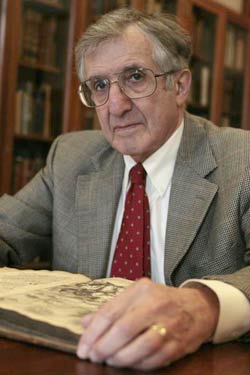

Paul Joel Alpers

Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1932 – 2013

Professor Emeritus Paul Joel Alpers, who served the Berkeley campus with great distinction for 40 years, died at his home in Northampton, Massachusetts on May 19, 2013. Born in Philadelphia on October 16, 1932, Professor Alpers completed his undergraduate and graduate work at Harvard, earning his Ph.D. in English in 1959. He came to Berkeley as an assistant professor of English in 1962 and was promoted to associate professor in 1968. In 1971 he became Professor of English, and in the following year was honored with a Distinguished Teaching Award. From 1980 to 1994 he was Professor of English and Comparative Literature, serving as chair of the English Department from 1980 to 1985. In 1994 he became the Class of 1942 Professor of English, the title he held at his retirement in 2002.

Paul was best known in the Department as a Renaissance scholar who specialized in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English poetry—particularly Spenser and Milton—but his literary interests were broadly historical. They stretched as far back as the mid-third century B.C., when the Greek poet Theocritus invented the pastoral eclogue; focused on Virgil in the first century B.C.; and extended through Italian, Spanish, and English writers of the Renaissance to novelists George Eliot and Sara Orne Jewett in the nineteenth century and poets Wallace Stevens and Robert Frost in the twentieth century. What linked these writers for Paul was his fascination with the pastoral mode as it recurred in many languages, genres, and styles across the centuries.

As a teacher Paul won early recognition for the way he showed his students how to read poetic texts that might initially seem alien, difficult, or off-putting, by paying close attention to word, image, and syntax--and by savoring the ideas and emotions they provoked. He was convinced that great literature has a special kind of complex intelligence that rewards the closest scrutiny and when taken seriously becomes, in Kenneth Burke’s words, “equipment for living.” And this meant that student writing about literature merited serious respect, too. He became known for scrupulous attention to his students’ essays and for an attitude that was rigorous, yet genuinely concerned to follow a student’s argument with patience and generosity, essential ingredients of his pedagogy. Engagement with literature, he believed, meant engagement with all its readers.

This disposition to treat his students as part of a larger scholarly community flowed into most everything he did professionally. He would, from time to time, invite a junior colleague to sit in on and contribute to his graduate seminars, and on one occasion, when a senior colleague’s seminar faced cancellation because it did not enroll enough students, he organized a group of faculty to “take” the course themselves, meeting weekly in the convener’s home to discuss the readings that had been prepared for the students who had not materialized. Not coincidentally, the convening of literary shepherds who sang to one another of their loves and social concerns in imagined communities became a focus of study in his two books on pastoral.

In the early 1980s he and a group of colleagues from English, History, Art History, and other departments in the College of Letters and Science met regularly at his home to exchange and discuss one another’s work and to talk about the directions in which humanistic studies were then moving. During the culture wars of this period Paul tended to seek out continuities—sometimes to the impatience of his interlocutors—in an ambiance where discontinuity was frequently celebrated as the new critical truth and it was fashionable to dismiss one’s critical forebears. Each break with tradition, he insisted, had to fully take into account what it claimed to be discarding, and was—like it or not—inextricably linked to it, however oppositional it might seem to its proponents.

These ongoing collegial conversations formed the seed-bed for a new intellectual enterprise, the interdisciplinary journal Representations, on whose editorial board he served from 1983 to 2002. His colleagues on the original editorial board of Representations recall his distinctive “pastoral” voice in a group largely dedicated to exploring new historical and theoretical approaches to culture—which were not central to Paul’s work, though his own ideas were historically and theoretically grounded. Indeed, he pursued what might well be called a “historical-theoretical-formalist-new critical-philological-conventionalist” approach to pastoral through literally exquisite readings of the languages, references, and attitudes he found migrating trans-historically in western culture. It is thus not surprising that his response to his colleagues’ often quite different work was supportive and critical. As Professors Catherine Gallagher, Stephen Greenblatt, Thomas Lacqueur, and Randolph Starn write in their remembrances of Paul for the journal: “Those basic things—deep learning, a gift for friendship and understanding of the importance of community, and an unbreakable trust in the truth-telling power and intelligence of poetry—characterized his singular place in Representations.”

Paul’s richly informed dedication to humanistic study made him a natural to become Founding Director of another enduring Berkeley institution, The Doreen Townsend Center for the Humanities, in which capacity he served from 1987 to 1992. From its inception, the Townsend Center has functioned as a lively interdisciplinary intellectual community that, unlike other humanities centers established in the 1980s to attract outside scholars to their campuses, draws primarily on the current research of Berkeley scholars. Each year the Center provides funding for Townsend Fellows who meet weekly to present and respond to one another’s work. Fellows include advanced graduate students, junior professors, some senior professors and, most recently, emeriti. In addition to these fellowship seminars, Paul instituted interdisciplinary team-taught graduate seminars, as well as conferences and lectureships, such as the Avenali and Una Lectures, which feature visiting scholars from the United States and abroad.

Paul’s own scholarship produced three landmark books and more than two dozen articles and essays. The Poetry of The Faerie Queene (1967) represented a major departure in Spenser criticism, which more often than not concentrated on explicating the poem’s allegories, exploring its narrative structure, and demonstrating its dramatic qualities. Without ignoring these features, he encouraged his readers to heed the surface of the text, that is, to allow the language of single phrases, lines, and stanzas to work on their sensibilities and then to register what work was being done. His was a rhetorical approach, in the most precise meaning of that term, concerned to make readers aware of the successive awarenesses that Spenser’s poetry was inducing in them. The book won the Explicator Award as the best book of explication published in 1967.

An accomplished Latinist, Paul turned in his second book to the subject that absorbed his attention for much of his later career. Although Virgil’s pastorals were deeply influential in the European poetic tradition, he was convinced that they were now virtually unknown except to classicists and decided to “make the Eclogues accessible to any serious reader of poetry, even those who know no Latin.” The result was The Singer of the Eclogues (1979), where he provided his own translations, along with the original texts and accompanying essays. This format enabled him to demonstrate and also argue discursively how Virgil represents poetic and social relationships through pastoral figures whose apparently idyllic settings are part of a Rome still suffering the political and social upheavals of civil war.

Paul’s last, magisterial, book, What is Pastoral? (1996), takes his earlier motive and runs with it. Beginning with Theocritus and Virgil, he argues that pastoral is not a representation of a naïve state of humanity or a sentimental kind of escapism from the complicated lives of writer and reader, but a mode in which herdsmen reveal the kinds of power human beings can exercise in relation to their respective worlds. Its primary convention is the convening of singers, talkers, and lovers from their rural labors—among them often the poet himself—to exchange experiences, compete in song, or lament personal and communal losses. The range of the book is astonishing, as is the suppleness of its concept, for Paul brings to our notice the shifting yet recognizably pastoral modalities of such disparate works as Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Wordsworth’s “The Ruined Cottage,” George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Thomas Hardy’s “Drummer Hodge,” and Frost’s “The Oven Bird”— by attending meticulously, as always, to the words. What is Pastoral? won the Christian Gauss Award of The Phi Beta Kappa Society in 1996 and the Harry Levin Prize of The American Comparative Literature Association in 1997.

Paul was awarded fellowships by The American Council of Learned Societies (1966-67, 1972-73); The Humanities Research Council (1970-71, 1985-86); The National Endowment for the Humanities (1979-80, 1992-93); The John Simon Guggenheim Foundation (1992-93); The Stanford Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences (1975-76); The Princeton Council of the Humanities (1980), and The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1996).

When he left Berkeley with his wife Carol Christ, who became President of Smith College, his life of fellowship continued in a new locus amoenus. He offered public lectures at Smith, organized faculty seminars, read colleagues’ work, and, like the perennial student he was, decided it was now time to take advanced courses in classical Greek. His immediate survivors include his wife Carol; sons Benjamin and Nicholas Alpers; stepchildren Jonathan and Elizabeth Sklute; four grandchildren; two brothers, David and Edward Alpers; and former wife, Svetlana Alpers. He is remembered with deep affection and admiration by his colleagues on the Berkeley campus who had the privilege of knowing him--and conversing.

Joel B. Altman