|

|

IN MEMORIAM

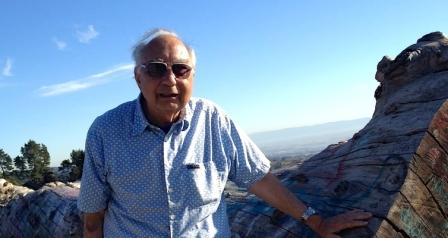

Charles Edward Murgia

Professor of Classics, Emeritus

UC Berkeley

1935 - 2013

Charles Edward Murgia died February 27, 2013, at his home in Oakland. He was born February 18, 1935, in Boston, where he attended Boston Latin School and Boston College and then pursued his doctorate in Classics at Harvard University. While still a graduate student, he taught at Boston College High School Summer School (1959), Franklin and Marshall College (1960-61), and Dartmouth College (1964-65). Immediately upon completion of his PhD, he joined the Berkeley faculty in 1966.

At Berkeley, Charles rose through the ranks in due order, attaining tenure in 1972 and promotion to full professor in 1978. He served as Department Chair from 1980 to 1983. In 1994 at the age of 59, he opted for early retirement in order to concentrate on his scholarship. For more than a decade after retirement he was frequently recalled to teach, especially the Classics Proseminar and Advanced Latin Prose Composition, and he also gave many presentations on Latin palaeography for Medieval Studies and the Proseminar. He also spent a semester as Visiting Professor at Harvard in 1996.

Although he originally had begun a dissertation on Thucydides and noted in his letter of acceptance to Berkeley in 1966 that he hoped he would be able to teach Greek courses from time to time, Charles was regarded locally and in the wider world as an extraordinary Latinist, with a consummate command of language, style, textual tradition, and textual criticism. His first and only book was the monograph Prolegomena to Servius 5 - The Manuscripts (University of California Publications: Classical Studies, vol. 11, Berkeley 1975), based on his Harvard dissertation. The large project expected from him thereafter was the edition that was supposed to follow of the Servian commentary on Books 9-12 of Vergil’s Aeneid. The main obstacle to completion was the impossibly high standard he set himself for the treatment of the testimonia to accompany the edition, and even when he was retired he was much happier working on other smaller projects than toiling over the testimonia for Servius. At his death, the edition was more or less complete except for the apparatus of testimonia and similar passages. He had collated many manuscripts, established their relationships, arrived at a near-final text of the commentary and critical apparatus (and decided how to display it typographically to distinguish the older Servian material from the expanded later version), and drafted introductory sections. His files and papers were left to the Department of Classics and are being organized with the hope that another scholar may be found to complete the edition.

Apart from Servian matters, Charles’ numerous articles touched on Vergil, Tacitus, Quintilian, Ovid, and Propertius. He was keenly interested in imitatio and allusion and developed a distinctive method of arguing for the relative dating of closely similar passages, including those in the same author when either the author is “imitating” himself or an inauthentic poem has entered an author’s corpus. Charles ran through the full cursus honorum of external research fellowships, earning awards from the America Council of Learned Societies in 1974, the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1979, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1983. He was a member of the Editorial Board of the top-tier American journal Classical Philology for almost thirty years.

Colleagues in the Department remember hearing Charles’ penetrating voice from down the hall, his hearty laugh, and the wickedly strong fishhouse punch he prepared annually in the days when parties at the annual meeting of the American Philological Association were held in overcrowded hotel rooms with liquor surreptitiously carried into the hotel. He was one of the earliest users of computers for his research, taking advantage of early UNIX and troff and a terminal with a special chip that allowed the use of Greek characters for his apparatus criticus. Another distinction during a long stretch of his Berkeley years was the presence of his mother, who moved from Arlington, Massachusetts, to live with her youngest son in his house in the Oakland hills. Mrs. Murgia often attended Departmental parties, and was always very happy to welcome the visits of the families of Charles’ colleagues who had young children.

Between his frequent offering of the Classics proseminar and his service in the Advanced Latin Composition course and other courses, Charles probably taught almost every graduate student in the Berkeley Classics program over the course of several decades. Graduate students’ most vivid memories of Murgia are usually related to his teaching them about the manuscripts and transmission of Servius in the proseminar or to his dissecting their efforts at Latin prose composition. Many recall the intensity and excitement with which he discussed Latin texts from Vergil to Tacitus in his seminars. And many tell stories of striking pronouncements and unselfconscious eccentricity that they witnessed in his office, at meals, or at parties. A typical anecdote recalled at the campus memorial gathering is that from Mary Jaeger (now Professor of Classics at the University of Oregon): "I learned a tremendous amount in his classes, and I use it every day, but Mr. Murgia was generous outside of class as well. I read Tacitus with him and two other graduate students in his office. Mr. Murgia would sit, slouched in his easy chair as we translated and discussed the Annals. As he became more and more interested in the text, he would slide lower and lower into his chair until he ended flat on his back on the floor, holding his book above his head. This sounds painful, but in fact, his office floor was well cushioned with drafts of articles and student papers."

Charles never married but had frequent interactions with his extended family as they moved west or visited the Bay Area. In his last decade he spent time every week with, and often vacationed with, his nephew Paul Doble and his wife Marie. Charles had been managing a heart condition after a difficult knee replacement surgery, but continued to be active. He had greatly enjoyed a vacation in Hawaii, one of his favorite destinations, that concluded just the day before his death.

Donald Mastronarde

Dylan Sailor